Pesach, or Passover in English, the eight-day festival commemorating ancient Israel's escape from Egyptian slavery, begins on Wednesday evening, March 27. The holiday's highlight is the Seder, a gala family meal that vividly recounts the biblical Exodus story through a combination of narration, prayer, food and music.

All leavened foods, especially bread products, are forbidden during Passover--a link with the flat bread or matzo the Israelite slaves baked during the Exodus when there was no time for normal preparation of food products.

Even in an age like ours when family members frequently live far from one another, Jews still make a modern pilgrimage to "come home" and share the Seder experience with relatives and friends. Indeed, the home Seder is one of the religious highlights of the year.

As a faithful Jew of his time, Jesus made a pilgrimage to the Holy Temple in Jerusalem to participate in his people's observance of Pesach. That is one reason the Christian holy days of Good Friday and Easter are coupled in time and place with Passover. Some scholars, both Christian and Jewish, believe the Last Supper was in fact the Seder dinner.

But behind the Jewish religious observance and the universal appeal of the holiday, certain questions remain to be answered. Did the Exodus really happen?

After all, the official Egyptian records from the period do not mention the Exodus. But that is no surprise. Why would a powerful and proud nation describe the escape of a downtrodden, despised group of slaves?

However, there is one specific Egyptian mention of "Israel," and it is on a victory stele or stone record from the year 1230 B.C. It boasts of the defeat of Egypt's enemies: "The Hittite land is pacified. Canaan is taken captive ... Ashkelon is plundered ... The people Israel is destroyed, it has no offspring ... The land has become like a widow for Egypt."

This is solid evidence indicating that the former slaves and their descendants had completed the 40 years of wandering in the Sinai wilderness and were already residing in Canaan, or what Jews call the land of Israel.

The Seder, one of the longest continuous religious observances in human history, is an annual remembrance of an event that took place about 3,200 years ago and remains a constant reminder that both the Egyptian chronicler and Stroop were wrong.

Another question: Why did the story of a ragtag group of slaves who fled from a mighty monarchy become a permanent part of the world's collective bank?

Throughout history, many oppressed peoples have used the Exodus as an inspirational model. It is no accident that Benjamin Franklin wanted the seal of the newly created United States to feature the Israelite slaves (independent Americans) fleeing Pharaoh's army (the British) as they crossed the Red Sea (the Atlantic Ocean).

It is also no accident that America's black slaves sang freedom hymns like "When Israel Was in Egypt land, Let My People Go!" and used the Hebrew Bible as a source of hope for freedom.

A final question: Why has the Seder meal endured so well and for so long? The answer is found in a bit of Hebrew grammar.

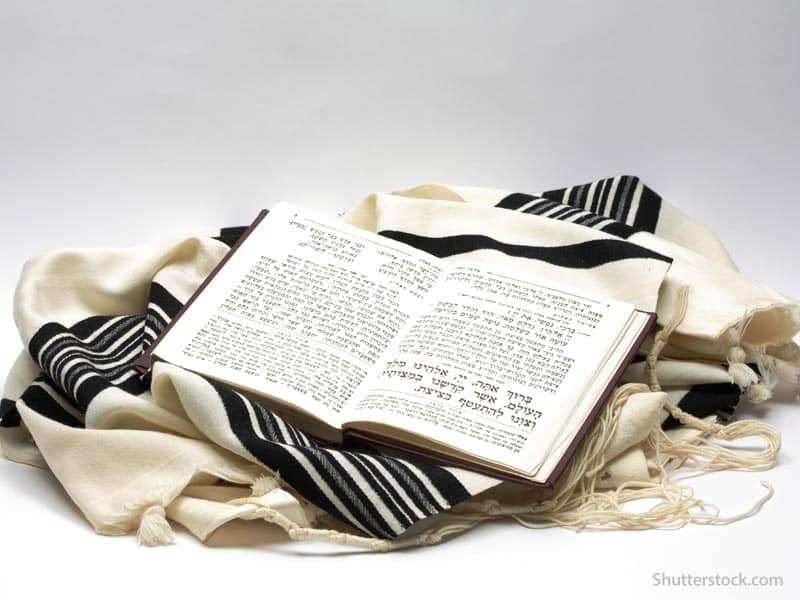

The Haggadah is the Passover narrative booklet read at every Seder, and probably began to be used in 13th century Spain. The Haggadah retells the Exodus in an unusual way. Instead of the conventional third person formula -- "The Israelites were slaves and they suffered..." -- the Haggadah text is filled with first person plural language: "This is the bread of affliction our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt ... We were Pharaoh's slaves in Egypt ... God brought us from the house of bondage ... In every generation we should look upon ourselves as if we came forth out of Egypt..."

The basic message is not subliminal, just the opposite. Participants sitting around the Seder table must link themselves with their ancestors of long ago. The bitterness of slavery and the exultation of liberation were not limited to the ancient slaves; today's Jews are inextricably linked to the same events.

It is the genius of the Passover Seder that modern users of e-mail and mobile phones connect spiritually and emotionally with their ancient ancestors who wrote on stone tablets and sheepskin.