Given that the Bible is the basis for the largest religion on earth, translating it correctly is obviously of extraordinary importance to an extremely large group of people. That does not mean, however, that there are not mistakes that happen when dealing with such an ancient document. Bible translations may be under more scrutiny than translations of many other ancient documents, but that does not mean that translators always get everything right. In fact, there are some words and phrases that people consistently mistranslate.

“Asherah”

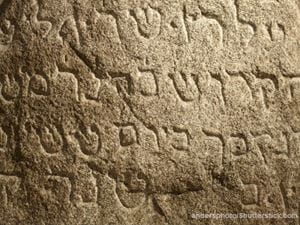

In the original Hebrew version of the Old Testament, the word “asherah” appears quite often, especially in stories involving the various kings of Israel and Judea. The most popular English translations, however, do not use the word “asherah.” In the places that it would appear, the King James Version tends to use “grove” or “graven image.” The New Revised Standard Version uses the phrase “sacred pole.” Both of these versions suggest that the “asherim” were idols of some sort. This is correct in the same sense that “water” is technically a correct translation of “ocean.” There is, however, a world of meaning missing from such a translation.“Asherah” does not simply refer to any idol. Asherah was a goddess from the ancient Middle East who was sometimes believed to be God’s wife. As almost every polytheistic god had a goddess associated with him, the ancient Israelites assigned Asherah to be God’s wife. The same goddess also appears in Hittite, Ugaritic and Akkadian writings. The fact that a foreign goddess had been adopted to be God’s wife helps show why the Old Testament warned against mixed marriages and explain why it was such a big deal that the “asherim” were in the Temple. This was not simply a matter of having a sacred object there. It was an issue of a foreign deity being adopted and her idol placed in God’s house.

“Ketonet Passim”

There are a handful of names that are repeated several times in the Bible. John and Mary are probably the easiest examples, but there are also a number of Joseph’s and Tamar’s. So, to differentiate which person is being talked about, there is usually some sort of identifier attached to their name. In the Bible, this is usually their birthplace or the name of one of their parents. In modern times, people tend to differentiate between biblical characters of the same name by referencing the story in which the person appears. One Joseph was the spouse of the Virgin Mary. Another Joseph is most often associated with his “coat of many colors,” later conceived of as the “technicolor dream coat” by Andrew Lloyd Weber. This distinctive item, however, has likely been misunderstood.In the original Hebrew, Joseph’s famous coat is said to be “ketonet passim.” “Passim” can be used to mean “colorful” but the phase is also used to describe a long garment that came down to a person’s hands and feet. Such garments were made of fine wool or silk and normally worn by royalty. Most importantly, this was not a garment that could be worn while working. As such, by giving Joseph such a garment, Jacob essentially declared that Joseph was too good to work in the fields. Joseph’s brothers took issue not with some colorful cloth, though dyed fabric would be very expensive and valuable, but with the clear declaration that he was of such a high station that he no longer had to join them in the fields.

“Lo Tirtsah”

The Ten Commandments are perhaps the most famous handful of verses in the Old Testament. Even when reading more modernized versions of the verses, such as in the New International Version, most people still default to the old fashioned language of the King James Bible. As such, one of the best known phrases from the Old Testament is simply “thou shalt not kill.” This famous line, however, has been mistranslated for centuries.The sixth commandment is written in Hebrew as “lo tirtsah.” The verb “ratash” does not mean “kill.” It means “murder.” There is a world of difference between forbidding any sort of killing and outlawing murder. Had this verse been meant to refer to any sort of killing, the word “harag” would likely have been used. Between the choice of word and the repeated discussions in the Bible of capital punishment, war and manslaughter, proscribing any sort of killing would make no sense. It would also be a death wish in the ancient world when survival often relied on very literally living out the proverb “if someone comes to kill you, rise early and kill him first.”

“Re’em”

When dealing with ancient documents, not all mistranslations are the translator’s fault. Sometimes, the problem is with the shifts in languages over thousands of years. This is the case with the ancient Hebrew word “re’em.” “Re’em” is usually translated as “wild ox,” though it has also been read as “unicorn.” The reality, however, is that both of these are the result of translators slapping in a word that sort of fits to take the place of something that no one can understand. The true meaning of “re’em” has been lost over the millennia. Context makes it clear that the word referred to an animal and that it was likely a four legged beast such as an ox. What creature it was specifically meant to describe, however, no one can say for certain. So, translators use whatever they feel fits best.“YHWH”

The Divine Name is another word that has only partially survived until the modern day. The four letters “YHWH” are well known to spell out at least part of God’s proper name. Most scholars believe this means the Divine Name was pronounced “Yahweh.” No one, however, can say this for certain. Ancient Hebrew has no vowels, so the correct pronunciation of “YHWH” would have been known only to those who had heard it spoken. Once it became taboo to say the Divine Name aloud, memory of its pronunciation would have faded quickly. As such, the places in the Bible where God’s actual name was written are normally replaced with the word “LORD” in all capital letters as no one knows for certain what else to add there.“Selah”

Some words survive at least partially today. Others remain complete mysteries. “Selah” appears over 70 times in Psalms and thrice in the Book of Habakkuk, but no one knows what this mysterious word meant to the ancient Israelites. Some claim that “selah” was mean to act as a line break in Psalms. Others say it meant “forever” or “to praise” and served a similar function to “amen” in modern churches. Yet another popular theory is that “selah” was meant as a form of instruction. Since the Psalms were originally written to be set to music and performed, many believe that “selah” was a form of musical notation for those who were playing an instrument or a sort of stage direction for the performers. No one, however, can say for certain what this mysterious word means.Translating ancient documents is never easy, and the cultural, historical and theological importance of the Bible puts a great deal of pressure on translators. They usually come through, but there are still some mistakes that are consistently made. That number has gotten fewer and fewer as translators have gotten better, but one cannot help but wonder what the Bible would look like if every translation somehow managed to be perfect. It would certainly have some interesting surprises.