In responding to Christianity, Jews historically have objected that the other faith gives too human a picture of God. Needless to say, as a Jew I’d have to agree. Yet nowadays from many Jews I find much less strenuous objection to spiritual ideas that picture God in a “refined supernaturalist” way, as William James put it, where He is reduced to little more than a vague vaporous abstraction, practically irrelevant to physical reality down here on earth.

Ironically, James observed that in his time, more than a century ago, Christianity itself was already heading in a perilously “refined” direction: “Odd evolution from the God of David’s psalms!” The trend persists in liberal churches, as in liberal Jewish groups.

This whole issue comes up in my work all the time. It is one problem with theistic evolution, as I wrote yesterday. Jews tend to be far more alarmed by intelligent design (ID), which as a kind of “crass supernaturalism” (James’s phrase, with which he also adorned himself) poses no such difficulty. Some of my fellow Jews are not shy about letting me know they think, in my association with ID, I’m guilty of something bordering almost on disloyalty to Judaism. If I identified with theistic evolution, that would be OK. Is this an authentically Jewish response from them? Obviously, I don’t think so. I will tell you why.

Did you ever wonder why the Hebrew Bible takes the risky strategy of using rampant anthropomorphism in describing God?

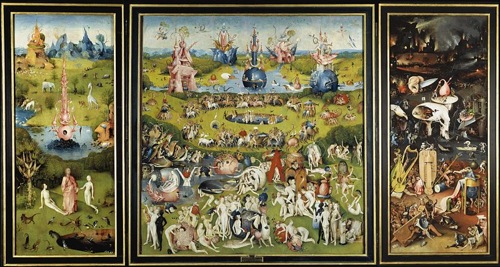

Here’s a classic case where God’s actions are humanized in a startling manner: “And they heard the voice of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day: and Adam and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God amongst the trees of the garden” (Genesis 3:8).

Huh? God takes leisurely strolls in the park? Yet Scripture also warns: “God is not a man, that he should lie; neither the son of man, that he should repent” (Numbers 23:19). So what’s up with that?

Commenting on one anthropomorphism in the Noah narrative, where God speaks “unto His heart” (Genesis 8:21), Rabbi S.R. Hirsch offers a surprising comment:

The danger of getting some corporeal conception of God is by far not so great as that of volatizing [that is, vaporizing] Him to a vague, obscure, metaphysical idea. It is much more important to be convinced of the personality of God, and His intimate relations to every man on earth, than to speculate on the transcendental conceptions of infinity, incorporeality, etc., which have almost as little to do with the morality of our lives as algebraic ciphers.

In depicting God, the Bible was faced with a dilemma. Humanize Him too much, and people may be misled in one direction. God then becomes not only a personality but a human person. That can’t be. Yet take the opposite tack, refining and abstracting Him, and we may be misled in the other direction. God then becomes refined out of existence, or at least out of any condition where He is relevant to our most intimate and personal lives.

Interestingly, recognizing the lesser of two dangers, the Hebrew Bible doesn’t opt for a compromise between the two. It totally rejects abstraction. So does the Talmud. Everything is disarmingly concrete. God interacts with creation in terms that sometimes shock us with their anthropomorphism. Rav Hirsch, I think, explains why.