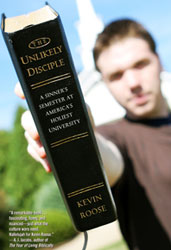

Kevin Roose was a junior at the Ivy League’s Brown University when he convinced his parents and his college dean to let him take his semester “abroad” at Liberty University, the conservative Christian school founded by the late Rev. Jerry Falwell. His book about the experience, “Unlikely Disciple,” is as remarkable for Roose’s acute observations about extreme evangelical culture as it is for his utter innocence about religion, at least when he stepped on the Liberty campus. I talked to Roose last week about his stunt, how it woke him up to other’s faith, and his own.

Kevin Roose was a junior at the Ivy League’s Brown University when he convinced his parents and his college dean to let him take his semester “abroad” at Liberty University, the conservative Christian school founded by the late Rev. Jerry Falwell. His book about the experience, “Unlikely Disciple,” is as remarkable for Roose’s acute observations about extreme evangelical culture as it is for his utter innocence about religion, at least when he stepped on the Liberty campus. I talked to Roose last week about his stunt, how it woke him up to other’s faith, and his own.

At the end of the book you seem to be cruising on the spiritual high you experienced at Liberty. Is that still happening?

Oh, absolutely. Before I went to Liberty, I was not an atheist, and I wasn’t Christopher Hitchens. I wasn’t a believer, either. I was just sort of God-ambivalent. I had no idea how powerful a faith community could be. Now I think about faith all the time. I try to pray every morning. It’s not that I have this cosmic expectation about the effectiveness of prayer, but it helps me get through the day. I’m still not to the point where that’s a perfectly natural thing. It still feels a little like I’m play-acting, but I’m going to keep at it for as long as it remains a positive force in my life.

You go back and forth in the book between an anthropological idea of faith, as something driven by intense community experiences, and something that lives inside of us. As you look back, where would you locate faith, especially the faith experience you had at Liberty?

I think it’s both. I think religion can’t exist in a vacuum. Religion thrives in community because you need constant reinforcement. You need people to question and push you forward. You need people to celebrate with. That group euphoria is not just a side benefit of faith. It’s a core reason that people are faithful. It’s going to be much harder for me to progress spiritually, in the Liberty sense at least, when I’m not surrounded by a community of believers. And I hope that in time I can find a faith community I’m comfortable with and that will kick start that process again.

Has anyone from a Christian group at Brown gotten in touch with you?

Actually they have. I met a young lady last night who is part of the–they call it College Hill for Christ, because Brown is located in [an area of Providence called] College Hill. They have reached out with gratitude that someone is finally acknowledging that, just as Liberty is not this monolith where all people think and believe the same thing, neither is Brown.

It’s a great question. A lot of us, especially people like me, we’ve barricaded ourselves in these communities where everyone agrees with us. It’s much more comfortable to be surrounded by people who believe the things that you do. It is, after all, why students go to Liberty–to be around people who have the same political, for the most part, and the the same theological beliefs for the most part. So, I think both sides are guilty of this sort of sequestering, and we need to do a better job of reaching across these lines.

Some people have pointed out, among them a Liberty professor, that in your portrait of the evangelical students you focus on things, like racism, that is not Christianity, but part of Southern culture, or Falwell’s particular politics. How do you respond to that?

Well, I tried really hard to keep those things separate, but it’s not always easy. Even evangelicals have a hard time separating the two strands. To a large extent, they’re the ones who conflated Southern culture and the evangelical faith, and given theological support to cultural ideas. I tried to say, “Okay, this is Southern culture, this is Jerry Falwell’s cult of personality,” but it’s hard even for evangelicals to do. I didn’t go to Liberty to get a macrocosmic view of all of evangelical Christianity. The point was to go to one specific community, and a very influential community.

A lot of time is spent talking about homosexuality in the book. Why do you think homosexuality is such a big deal?

I think it has a lot to do with the Moral Majority’s evangelical trinity of abortion, gay marriage, and school prayer. Homosexuality was not something that I necessarily wanted to focus on, but there was just so much talk about it, more than places where gay people exist in the open. In rendering my semester faithfully and to scale, I had to include some of that stuff. It was just all over.

But did you ever get a sense of why?

Well, a lot of Christian kids are also asking themselves, why–why is this considered the biggest threat? Why is it more important than helping the poor or living a life of service? I never found a satisfactory answer. I think some of it is genuine belief that this is what the Bible says about a man and a woman being the only acceptable form of romantic union. And I think that’s totally valid. I don’t think that all people who are opposed to gay marriage are blazing homophobes. People who make a good faith attempt to understand this stuff still come out on the side that the Bible forbids homosexuality. What was interesting is that [at Liberty] it’s okay to believe that gay marriage is wrong and that homosexuality is a sin, but if you start dwelling on it, people start to wonder what your problem is.

At the end of the book, you say the younger Falwell may be taking Liberty in a less rigorous direction. In what sense?

I don’t think that Jerry Falwell, Jr., is any less conservative than his father. But he belongs to a different generation of evangelicals, and the differences between those generations are pretty stark. I’ve had only limited contact with Jerry Falwell, Jr., but in my experience, he’s not a reactionary. He’s not a demagogue. He has no interest in being a political force. He wants to run his university and have his students growing in their education and in their spiritual lives. But when I go back to campus now, there’s just a new energy. They’re doing a lot more community service now. They’re taking their faith to places in the culture where it’s needed.

You have a lot of fun with your creation studies class in the book. Did you get the sense that your classmates were rolling their eyes as well?

I think some of them actually thought it was sort of embarrassing. It’s something that I think discredits a lot of what the institution does in the public’s eye. But, I do think that a lot of them believe it some, not because it’s easy, but because they’ve been told that it’s sort of a foundational part of their Christian faith. If they start questioning Creationism, then that will lead them down the slippery slope, and they will soon become like Richard Dawkins. They’ll be just this heathen. There a lot of questioning, especially late at night in the dorms about whether evolution was true and what would it mean if it were. But if you ask them at the end of the day to check off a box, about which creation story they believe, I think they would all check the young earth creations box.

In your book tour, have you visited any other Christian colleges?

No. I would love to. I’ve actually heard from a couple graduates of more moderate Christian colleges who say, “This isn’t what my college experience was like, and I wish you’d come out and spend a semester here and get a different picture.” And I think if my parents wouldn’t kill me, I would think about it.