The epics and sacred texts of India are filled with dreams.

The epics and sacred texts of India are filled with dreams.

They involve scary things – being robbed, being attacked by a wolf, being raped

– that can spill over into waking reality. The verses include formulas of

protection, to turn away the evil seen in a dream.

If someone I have

met, o king, or a friend has spoken danger to me in a dream to frighten me, or

if a thief should waylay us, or a wolf – protect us from that, Varuna. [Rig Veda]

The Upanishads describe four

states of awareness: waking, dreaming, dreamless sleep – all natural and

available to all – and a transcendent fourth state of identity with the divine,

which requires illumination. It is now made clear that through dreaming, we can come into contact and alignment with the god who creates

us by dreaming us into existence.

The Brhadranyaka Upanishad, or “Great Forest Book”, is one

of the oldest Upanishads, dating from the 7th century BCE. Here dream state

is described as a state of “emitting” [srj], a word

that can also mean the ejaculation of semen. The dreamer “emits” or projects

from himself “joys, happinesses and delights…ponds, lotus pools and flowing

streams, for he is the Maker.” We learn here that as we grow the practice of dreaming, we can create realities.

In a beautiful passage in the same Upanishad, the dreamer travels between worlds as “the lonely swan”, flying in and out of the nest of

the body.

The dreamer is godlike in his ability to create in

the dreamspace: “In the state of dream going up and down, the god makes many forms

for himself, now enjoying himself in the company of women or laughing or even

beholding fearful sights.”

A Sanskrit name for dream

travelers, kamacarin, means “those

who can transfer themselves at will”. The literature and sacred writings of India are a

treasury of tales of dream travel, clearly grounded on experience.

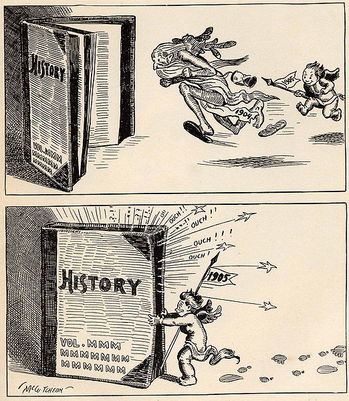

The Yogavasistha, a vast Kashmiri compilation,

is one of the richest troves. In these

narratives, dream travelers find that time is elastic. You may live a hundred

years in a dreamworld and return to find that only a day has passed in ordinary

time.What is

experienced in the dreamworlds is real, and has real consequences in the

traveler’s ordinary reality. Spiritual apprenticeship and initiation can take place in this

way.

In another Hindu story, Markandeya is a human

being who is curious about what is real. He tries so hard to see beyond the

obvious that one day, without meaning to, he falls out of the mouth of Vishnu,

the dreaming god. He now discovers that he has spent his whole lufe inside the

body of the god. Now he’s out there, he has a cosmic vision of the structure of

the universe; he sees that everything he knew is contained within the body of

the dreaming god. But this vision is too much for him; it inspires him with a

trembling awe that easily shifts to terror. It’s too much for him, even though

he is an evolved soul, an adept. So he climbs back through the mouth of Vishnu,

back into the world he contains, and as he resumes his life there he starts to

forget what he saw beyond it.

Ayurvedic

physicians maintain that we are deluded if we believe that we are fully awake

and conscious in our everyday lives. At all times, we are actually in a state

of dreaming. Enlightenment and healing become possible when we awaken to the

reality that we are continually dreaming.