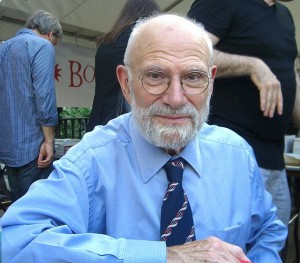

This is a post about sharing. About a man who has inspired me for a long time, and his impending loss. It’s about intelligence, wit, and vulnerability. And the irreplaceable magic of those braided qualities. It’s about making a good life, and a good death.

I don’t know when I first discovered Oliver Sacks. Perhaps even before the famous ‘Awakenings’ movie. I know I’ve read so many of his books that I can’t remember which I haven’t, as I also read any reviews of him, or his work, that I come across.

He’s an enchanting mix of brilliant intellectual, curmudgeon, and polymath. Writing about music, neurology, hallucinatory drugs, sign language or his uncle, he never disappoints.

But one of his biggest draws, to me, is his willingness to show his ‘flaws’ in his personal writing. From reading his various books & articles, I know quite a bit about Dr. Sacks: the sadism of his childhood education, his geekiness over chemistry, his fascination with language. I know that he suffers from prosopagnosia, a syndrome where he can’t recognise faces, and that he views his terminal shyness as ‘a disease.’ He’s written about his celibacy — that he hasn’t had a relationship in years.

This non-attachment to a ‘perfect’ public self strikes me as magical. It’s so very hard to reveal your fallibilities to the world at large. Not only has Sacks shared these vulnerabilities, he’s also left himself open to some pretty mean criticism. Is he perfect? Of course not. But if you read the various negative critiques, many sounds more like sour grapes than legit analyses of content & research.

Why a man I’ve never met feels like a kind of mentor isn’t really the reason I write this post. It’s more that for those of on this rocky, labyrinthine journey of beginner’s heart, opening up is often more difficult than anything. Acknowledging our flaws — much less putting them out there for strangers to poke through! — is so hard. If I can’t forgive myself for my sharp temper, my impulsive actions, why would I think you can? If my tendency to dismiss those I disagree with is hard for even me to accept, how can I believe you’ll still love me if I highlight it? Self-compassion is as hard as climbing Everest…

But Sacks has done this — forgiven himself — and more. Most recently, he’s written his own eulogy of sorts, a graceful tip-of-the-hat (which he still wears) to the knowledge that he has only months left. Since — as he notes — he’s 81, he isn’t bemoaning the unfairness of his ‘short’ life, a life lived out loud, and through a lens of wonder. Still, to live w/ the knowledge of imminent death is different than the backdrop of mortality upon which all our lives are silhouetted. I rarely think I might die tonight. I suspect Sacks has far more of those moments these days.

Once more my mentor is showing me the way, reminding me that any day might be the last. That I need to let the people I love know this, and make every day count. That I should begin now to ‘make a good death,’ as Buddhists (& others) urge. Which requires my life becoming a ‘good life.’ And I know, it’s kind of hokey. What’s ‘good’ about death? Well, the opportunity to reflect and forgive, certainly. Again — it’s not forgiving my father for being gone that’s hard. Or my mother for the one time she slapped me (one!). Or even the once-best friend who betrayed me. No, a good death is about forgiving myself. About making peace w/ those I feel I’ve wronged, and letting go of my attachment to my own guilt. This is what Sacks is, once again, teaching me. And I’m so grateful.

Go with grace, Dr. Sacks. You deserve a good death as the finale to a very good life indeed. We’ll miss you.