“Pauli Effect” is a term used for the mysterious malfunctioning of equipment in the presence of a certain person. We all know someone who has this effect, stopping watches, crashing computers, blowing out light bulbs. Often the phenomenon looks like a kind of adult (or not-so-grown-up) poltergeist sydrome, in which someone’s roiling emotions effect electro-mechanical functions as well as human interactions.

“Pauli Effect” is a term used for the mysterious malfunctioning of equipment in the presence of a certain person. We all know someone who has this effect, stopping watches, crashing computers, blowing out light bulbs. Often the phenomenon looks like a kind of adult (or not-so-grown-up) poltergeist sydrome, in which someone’s roiling emotions effect electro-mechanical functions as well as human interactions.

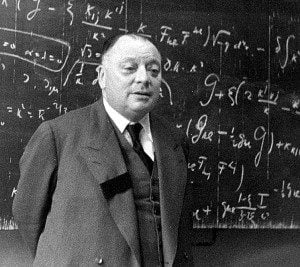

Let’s take a look at the man for whom the Pauli Effect was names, the brilliant pioneer of quantum mechanics, Wolfgang Pauli, whose long-time dialogue with Jung contributed to the great psychologist’s theory of synchronicity. Over many years, Pauli’s colleagues credited him with the tendency to cause things (especially physics experiments and equipment) to blow up, with no damage to himself. At least one experimental physicist, Otto Stern, banned Pauli from coming anywhere near his laboratory.

Pauli’s friend and colleague Rudolf Peierls described the Paul Effect as follows: “This was a kind of spell he was supposed to cast on people or objects in his neighborhood, particularly in physics laboratories, causing accidents of all sorts. Machines would stop running when he arrived in a laboratory, a glass apparatus would suddenly break, a leak would appear in a vacuum system, but none of these accidents would ever hurt or inconvenience Pauli himself.”

When important experimental equipment in Professor James Frank’s laboratory at the Physics Institute at the University of Göttingen blew up for no apparent reason, someone remarked that this could be the Pauli effect. However, Pauli was nowhere in the area; he was on a train, traveling to Denmark. It was later discovered that at the time of the lab explosion, the train carrying Pauli from Zurich to Copenhagen was making a stop at Göttingen station.

When he arrived at Princeton in 1950, an expensive new cyclotron that had recently be installed burned for no obvious reason, and there was again speculation about the Pauli Effect.

Such phenomena happened outside the laboratory.

When the Jung Institute was inaugurated in Zurich in 1948, Pauli attended the opening ceremony, since Jung had asked him to become a “scientific patron” and so represent the convergence of physics and psychology. At the time, Pauli’s mind was turnng on the tension between two earlier approaches to knowledge represented by the alchemist Robert Fludd and the scientist Johannes Kepler. When Pauli entered the reception room for the Jung party, a large Chinese vase inexplicably slid off a table, creating a flood that drenched some of the distinguished guests. Pauli saw huge symbolic significance because of the echo of “Fludd” in the phenomenon of the spontaneous “flood”. This incident inspired him to write his paper “Background Physics”.

On another occasion, Pauli was sitting at a table in the window of the Café Odeon, thinking intently about the color red and its feeling tones. While thinking “red”, he was unable to take his eyes off a large, unoccupied car parked in front of the restaurant. As he watched, the car burst into flames and his field of vision was filled with fiery red.

In yet another, quite hilarious, incident in New York, Pauli was lunching with Erwin Panofsky, the famous art historian and two other scholars. When they rose from the table after dessert, three of the men found that they had been sitting – inexplicably – on whipped cream, now smeared over their trousered rumps. The only one unscathed, of course, was Pauli.

According to his close colleague Marcus Fierz, “Pauli believed thoroughly in his effect.” He experienced an unpleasant inner tension before things blew up. After the event, he felt relief and release from tension, even moments of euphoria. No doubt he enjoyed his ever-growing reputation for producing wickedly strange phenomena. This was, after all, the man who dressed up as Mephistopheles for a skit in front of Niels Bohr’s circle in Copenhagen.

The best story on the Pauli Effect is from Rudolf Peierls, a German-born physicist who moved to England and later worked on the Manhattan Project. Some of Pauli’s fellow-scientists plotted to spoof the effect attributed to him at a reception. They carefully suspended a chandelier by a rope that they intended to release when Pauli entered the room, causing the chandelier to crash down. “But when Pauli came, the rope became wedged on a pulley and nothing happened – a typical example of the Pauli effect.”

It has been suggested that the reason Pauli was not invited to join the Manhattan Project – which recruited many physicists from his circle – was that the directors knew Pauli’s reputation and were worried that he would blow up something vital.

Adapted from The Secret History of Dreaming by Robert Moss. Published by New World Library. Source notes for this article will be found in the book.