Case in point: The gorgeously produced 1998 animated film "Prince of Egypt," with Moses as its hero, completely missed the significance of the Passover story. The film ends in just the wrong place after Moses has split the Sea of Reeds, letting the Jews pass through safely before the walls of water collapse upon the pursuing Egyptian army. It is depicted as the story's denouement, toward which everything else was leading.

Hollywood is not alone in misunderstanding where the Exodus story's climax belongs. Many Jews, and others, see the liberation of the Israelite tribes from Egyptian slavery as the whole point of the Passover narrative. <>

Not so at all. The purpose behind God's redeeming of the Israelites can be summarized in a word, and a holiday: Shavuot.

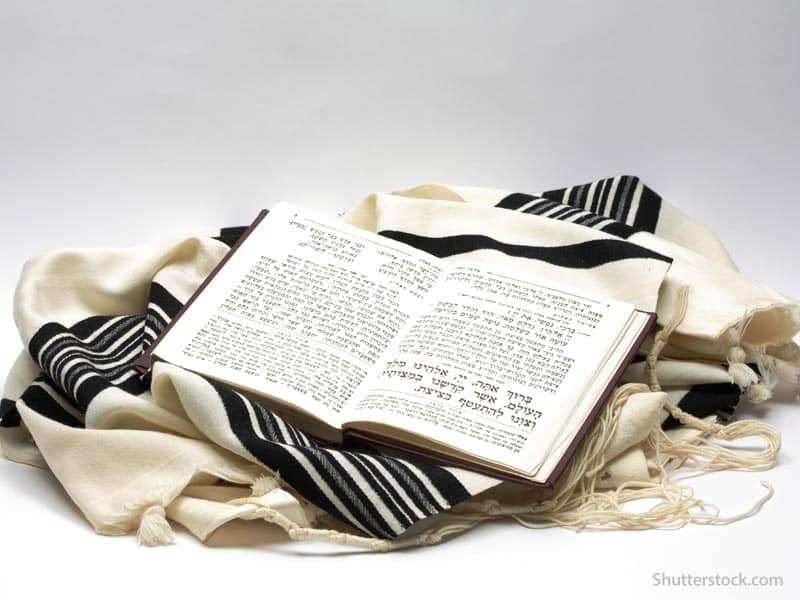

In contemporary America, Shavuot is certainly the least observed of Judaism's biblical festivals. It comes on the sixth of the month of Sivan seven weeks after Passover and celebrates the giving of the Torah and the 10 Commandments to Israel at Mt. Sinai, an event that occurred some 50 days after the Exodus. That event, and not the picturesque crossing of the Sea of Reeds, was the climax toward which the Exodus led the children of Israel.

The two holidays are so closely linked in significance and in Jewish liturgical practice that at the conclusion of the seder meal on Passover's second night, Jews formally begin the counting of the omer (an ancient unit of measurement), a ritual dating back to the days of the Temple in Jerusalem that serves as a countdown of the days that will conclude on Shavuot.

The Torah is the commission from God to the Israelites to be His "kingdom of priests" (Exodus 19:6), with all that entails by way of the unique grammar, that is, the mitzvot, or commandments. It is the covenant that created the Jewish people out of the Israelite tribes and defined the Jews' relationship with God. In the scheme of world history, were it not for the revelation of the Torah at Sinai, were it not for Shavuot, the Exodus and its commemoration at Passover would have been of little significance.

True, one of the most beloved songs of the seder's liturgical script is called "Dayenu." In Hebrew, that word means literally, "It would have been enough for us." (Hebrew is a compact language, often requiring only one word to say something that in English would take a whole sentence.) "Dayenu" includes the puzzling line, "Had He [God] brought us before Mt. Sinai, but not given us the Torah, it would have been enough for us."

What? Didn't I just say that freeing us from Egypt would have been pointless had God not then given us the Commandments?

But would it have been enough for God, or for humanity, if the Lord had merely brought us up from Egypt and left us, free, at the foot of Mt. Sinai without giving us the Torah? Human history was meant to be the history of our priesthood in service of mankind. The foundation, the constitution, of our priesthood is Torah. For mankind, a Jewish people freed from slavery but unacquainted with Torah would not have been enough.

That is why Passover is so insistently linked with Shavuot. This, incidentally, helps makes sense of the overall structure of the Jewish religious calendar, which revolves around two clusters of holidays separated by six months, each cluster associated with one of Torah's distinct "new years." One Jewish "new year" comes in the spring with Passover followed by Shavuot. Another "new year," in the autumn, commences the other festival-cluster: Rosh Hashanah followed immediately by Yom Kippur followed immediately by Sukkot.

To put the matter simply: The first cluster (Passover-Shavuot) is about origins-the origins of Torah, hence the birth of the Jewish people whose identity is defined by Torah. The second cluster (Rosh Hashanah-Yom Kippur-Sukkot) is about continuity: "Now that we're Jews, what are we supposed to do?"

At Rosh Hashanah, God evaluates our performance as His partners in the covenant of Torah. At Yom Kippur we renounce our actions that amount to violations of the contract with God and resolve to improve our level of compliance. At Sukkot, we appreciate God's tender protection and abiding love despite our failures, which is the reason behind our spending the week of this most joyous of festivals camping out in huts (in Hebrew, sukkot), unprotected by the sheltering architecture of our permanent dwellings.

Sukkot is also the apocalyptic Jewish holiday, anticipating the time when the priestly purpose of Jewish existence will be fulfilled, with the world's peoples coming up to Jerusalem's rebuilt Temple "every year to worship the King, the Lord, Master of Legions, and to celebrate the festival of Sukkot" (Zechariah 14:16).

When you step back to a contemplative distance and observe the integrity of the Torah's calendar, it becomes obvious why leaving out any part or element in the whole, perfect structure-like, for example, venerating Passover but blowing off Shavuot leads to the structure's collapse.

I suspect that this joyous, awe-inspiring, and crucially important day is largely ignored in American Jewish culture because its message makes many contemporary Jews uncomfortable. More than any other festival, it calls us to accept all the ramifications of our commission by God to be Jews-specifically, adherence to the 613 commandments given at Mt. Sinai.

The joys of the eternal Sinaitic covenant ascend to heaven, but the responsibility to follow Jewish law (halakha)-a body of legislation still being clarified and applied by Jewish sages to unprecedented modern circumstances down to our own day isn't compatible with every lifestyle, to put the matter mildly.

As 20th-century Jews entered the dominant culture's mainstream, they found it increasingly difficult to adjust their lifestyles in accordance with the mitzvot. So our grandparents and great-grandparents increasingly shunted Shavuot into obscurity, leaving their descendants-us-Jewishly bereft and impoverished without knowing it.

Jews aren't alone in our misunderstanding of Passover. In this respect we are joined by Christians, among whom the holiday has lately experienced a startling new popularity unknown since the first centuries of the Common Era. Back then, Christian authorities had to warn Christians not to observe Passover the threat of "Judaizing" was considered that severe.

Passover is the Jewish festival that Christianity has sought to take over and adapt as its own. Easter began as the Christian Passover, for good scriptural reasons having to do with the fact that Jesus died at Passover time, and the possibility that his last meal was a Passover seder. Easter used to coincide precisely on the Christian calendar with Passover until Constantine's calendrical reforms. In Christian theology and iconography, Jesus is regarded as the ultimate Passover sacrifice (John 19:36)-Jesus, this man who inspired a religion that gave Jews of his time what some (those who didn't reject him) took to be an honorable discharge from the Sinai covenant.

If Passover is the holiday par excellence that focuses us on the tension between Judaism and Christianity, it also suggests possibilities for resolving the tension. We live in a time of extraordinary Judaizing by Christians, especially among American evangelicals who are bursting with curiosity about Jesus' Old Testament background.

Christians hold seders and read books like Michael Smith and Rami Shapiro's Let Us Break Bread Together: A Passover Haggadah for Christians, Beverly Jeffers's A Christian Observance of Passover, Joan R. Lipis's Celebrate Passover Haggadah: A Christian Presentation of the Traditional Jewish Festival. We seem to be witnessing the emergence of the repressed Christian Passover.

Why should Christians find it "wonderful" to consider an alternative to their own notion that for all people, including Jews, adherence to religious law (as in Judaism) is a lame substitute for a religion of faith (like Christianity)? First of all, Judaism is a religion of faith, albeit one where faith takes concrete expression in the form of the commandments.

But you might still ask what could be so pleasing for a Christian about giving up the idea that faith-entirely and in all cases trumps adherence to law. After all, that idea was at the heart of the apostle Paul's brilliant marketing strategy, and it still pulls in converts two millennia later.

The answer is that for almost 2,000 years, the Christian soul has been haunted by the Jewish problem: what to make of the fact that the Christian savior's own people, who presumably knew him best, rejected him. Didn't the Jews' rejection cast doubt on the Christian assertion that Jesus was the Jewish messiah? Refusal to accept the reasoning behind the Jewish rejection of Jesus has led Christians to devise various tortured theories explaining the mystery of the continuing existence of Judaism and of the Jews, and to the projection of Christian perplexity in the form of anti-Jewish violence in the Crusades, the Inquisition, etc. Christianity is still in need of a scripturally based reconciliation with the special role of Jews in the world, a role defined by Jewish law.

As early as the New Testament's letter to the Hebrews, Christians were quoting the prophet Jeremiah's famous but enigmatic statement that God would "establish a new covenant [brit chadashah] with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah" (Hebrews 8:8 citing Jeremiah 31:31)-as if this pointed to a new law for the Jews (in the form of Christianity) destined to replace that of Sinai.

It pointed to no such thing. In Hebrew, a covenant (brit) designates only the commitment to the content of the agreement between parties, not to the content itself. In other words, the establishment of a new brit only signals that the Jews, in the messianic era, will recommit themselves to the ancient, eternal Sinai covenant. This is why the Torah (Deuteronomy 28:69) speaks of God having established two distinct covenants with the Jews during the 40 years after the exodus from Egypt: one at Sinai, the other in the plains of Moab, where Moses, before he died, recapitulated the teachings the Jews had received from God at Sinai. The content of each covenant was exactly the same. They differed only in the fact that the Jews in each case made a new commitment to observe the same body of law.

The relationship between God and the Jews, with its unique grammar of moral, legal, and philosophical teachings, is eternal and unchanging: This thought, I believe, could set Christian hearts at ease. Yes, there are solid scriptural grounds-notably the linking of the biblical festivals of Passover and Shavuot even for a Christian to believe that the Jewish covenant with God goes on.

Jews could help to spread the word among our Christian neighbors, giving them comfort, correcting the misunderstanding, if only we ourselves understood.