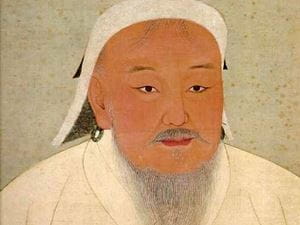

You know him as a conqueror. You know him as the man who killed fully 5 percent of the world’s population through a brutal series of wars that carved out what was, for a time, the largest contiguous empire ever seen. And indeed, Genghis Khan, the founder of the mighty Mongol Empire, was all of these things.

Consider this quote, attributed to Khan in the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh.

“The greatest happiness is to vanquish your enemies, to chase them before you, to rob them of their wealth, to see those dear to them bathed in tears, to clasp to your bosom their wives and daughters.”

If that quote sounds familiar, it’s because it was repurposed in the 1982 film, Conan the Barbarian, famously said by Conan, a brutal warrior, when he is asked, “What is best in life?”

But what if you found out that Genghis Khan, in addition to being all of this, was a champion of religious freedom, and that his legacy affected America’s founding fathers?

The Conqueror

Genghis Khan was a military genius, able to create fear, which spread before him like a disease, infecting and weakening his enemies. The impending arrival of his Mongol hordes caused absolute terror—a terror he crafted as only an artist could.

Born in 1162, Khan arose from a disgraced and exiled family, growing up in a desolate place where provisions were scarce. Few could have guessed that he would grow into an unparalleled warrior who would go on to establish one of the largest land empires in history, uniting the warring tribes of the Mongolian plateau and conquering large swaths of central Asia and China.

At its largest, the Mongolian Empire was comprised of about 12 million square miles of territory.

Khan did this through the complete devastation of his enemies. It wasn’t enough for him to win—he shattered, leaving nothing behind but crows and wolves in those places that felt his hand of judgment. Subjugated cities had to take care—a single act of resistance would immediately bring down that hand.

No tactic was too gruesome for the founder of the Mongol Empire. Khan was known to catapult diseased bodies into enemy cities, causing massive casualties when that disease began to spread. The use of such methods is thought to have begun the Black Death in Europe.

In the face of all this, most enemies willingly bent the knee to Genghis Khan rather than joining the more than 40 million dead at his hand.

The terror of this razor-edged choice between death and alliance was what drove Khan’s conquests—when foreign leaders heard what happened to neighboring cities when they resisted, they were much less likely to resist, themselves, especially when Khan promised protection and relative independence upon surrender, as long as they agreed to pay regular tributes.

And so with fear going before him like a plague, Khan made full use of what we would call psychological warfare, destroying certain populations so that the rest might be tamed, made subordinate to Khan, and become an additional source of income.

With all this, Khan’s forces became an unstoppable engine of war.

The Leader

As great a warrior as Genghis Khan was when in the saddle of a warhorse, he knew that an equal amount of skill must be applied when governing on the ground—it was from this attitude that Khan’s revolutionary ideas of religious freedom flowed.

Khan knew that slavery and utter subjugation were not the path toward a stable empire, and so he allowed relative autonomy in those kingdoms he defeated. As we’ve learned, Khan’s deal was all-or-nothing—even the barest hint of resistance was met with total destruction. Alliance, though, was met with striking equality.

Khan’s kingdom was a meritocracy—people were promoted and given positions of power based on skill, experience, and talent rather than heritage or class. This was a huge break from tradition, at the time, and gave Khan an advantage—his armies were made up of those who were best at shedding blood, not of those who were merely of the best blood.

Because of this, Khan frequently made officers of his most powerful enemies. In one famous story, Khan’s horse was shot out from under him during a battle. After his forces triumphed, he lined up his enemies and demanded that the soldier who loosed the arrow reveal himself. When the soldier boldly stood and proclaimed himself the shooter, Khan made him an officer and gave him the nickname “Jebe,” which means “arrow.”

Jebe went on to be one Khan’s greatest and most feared field commanders.

Khan’s attitude toward equal opportunity extended, most notably, to religious worship, and he enthusiastically embraced the diversity of his many conquered lands.

As his empire grew, Khan began to pass laws that established religious freedom for all citizens and granted tax exemptions for places of worship.

The Mongols were extremely open-minded in their views toward religion, openly embracing the existence of Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, and pagans. This was partly to ensure the happiness—and resulting passivity—of conquered peoples, but also because of Khan’s intense interest in spirituality. He had a great love of philosophy, and in much the same way he assembled his government and armies, he assembled philosophical and spiritual knowledge, picking what he felt was the best and incorporating it into his worldview.

It was this habit that would, strangely, find its way to America during the revolutionary period, perhaps paving the way toward the nation’s embrace of religious freedom.

Champion of Religious Freedom

George and Martha Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and major parts of the populations of revolutionary Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia, were obsessed with the story of Genghis Khan.

While it may sound odd for these early Americans to so love a Mongolian warlord who took millions of lives, the country’s rebellion against English rule created a peculiar craving. They sought out historical models for their new country outside of traditional Christian, European history—this simply didn’t work for them, as the American colonies were comprised of opposing religious sects and political dissenters.

What they found was the story of Genghis Khan.

Soon, his biography became popular. It was in George and Martha’s library. Ben Franklin sold his own copies. Plays about Khan were put on across several states. Khan’s style of governance had reached out from the 12th century, and into the 18th.

His success in both taming religious extremism, and in creating an empire out of a patchwork of beliefs, attitudes, and worldviews, made him a hero amongst American rebels—particularly to America’s founding fathers.

Thomas Jefferson adored a French copy of Khan’s biography by French scholar François Pétis de la Croix, and was fascinated by Khan’s allowance not only of certain religious traditions, but of total freedom of religion at the individual level.

It so it was that the example of Genghis Khan, the destroyer of millions, became the model the Virginia law of religious freedom—the first of America’s religious freedom laws. In fact, Jefferson’s wording almost exactly paralleled that of Khan’s, as it was written in the French biography.

The Legacy of a Warlord

Who would have ever thought the words of a man who flung diseased bodies over walls, killed so many people that weather patterns were disturbed, and who utterly mastered the art of fear, would form such an important part of the foundation of our nation?

They did, though, and so the next time you head to church, you might want to give a little thanks that famed leader of the Mongols.