Professor Richardson, who taught New Testament at the University of Toronto for many years, had invited me to join eight other Old and New Testament scholars on the Advisory Board of Visual Bible International, a company that makes Bible spectaculars. VBI had already made a few word-for-word films of New Testament books, but recently the company had brought in a new team headed by Garth Drabinsky, producer of the Broadway shows "Ragtime," "Show Boat," and "Kiss of the Spider Woman."

In May 2002, Garth, the creative team and the advisory board met in Toronto to make lists of books of the Bible that could readily be adapted to the screen. The Gospels got first priority, since they are so beloved and have narrative unity. Exodus, too, seemed a natural, but we realized the end of the book, with its laws and provisions for the tabernacle would be hard to film, and we postponed it for later. Filming Paul's Corinthian correspondence intrigued us, but the screenplay would be very tricky. In the end, we put two less often depicted Gospels-Mark and John-at the top of our list, followed by 1 and 2 Samuel. We still revisit the question frequently in our meetings.

The Gospel of John was chosen to be made first. A year and a fraction after that first meeting, a large number of very creative people had produced a professional retelling of the Fourth Gospel. Garth's experience and his drive for perfection was behind not only the amazing speed but the high production values. He had hired well-known professionals who in turn lured a superb cast. The set designers had found excellent locations in Spain (computer graphics fill in the shots of ancient Jerusalem) and built sets on giant soundstages back in Toronto.

In the planning period, we had assumed we'd be producing mostly for churches and synagogues, with an occasional commercial release eventually. Now we knew we had our first commercial release.

The Good News Bible translates "Ioudaioi" in Greek often as "Jewish leaders" or "Jewish authorities," and suggests the ambiguity of the word "Jew" in the first century, which could refer to a religion, an ethnic group, or even merely an inhabitant of a geographical locality.

We also asked that the casting emphasize people of appropriate coloring and features for the Eastern Mediterranean basin at the time. This, we thought, would include people with very dark complexion as well as medium complexions. This gave the film a feeling of a family feud, rather than a battle between religions. We felt some of the Romans might be depicted with fairer features or darker features because Rome encouraged military service throughout the Empire.

We also tried to give the creative staff an idea of the Johannine perspective. John makes Jesus divine from the very beginning of his gospel. (Notice how Jesus speaks in long, coherent discourses.) The Fourth Gospel considers Jesus' crucifixion and death the beginning of his victory and his exaltation, not a moment of anguish and despair. (Music played an important part on that point.) The creative team found many things of interest on their own. Indeed, the process of bringing the Gospel to the screen gave all of us new insights into what the Gospel really means.

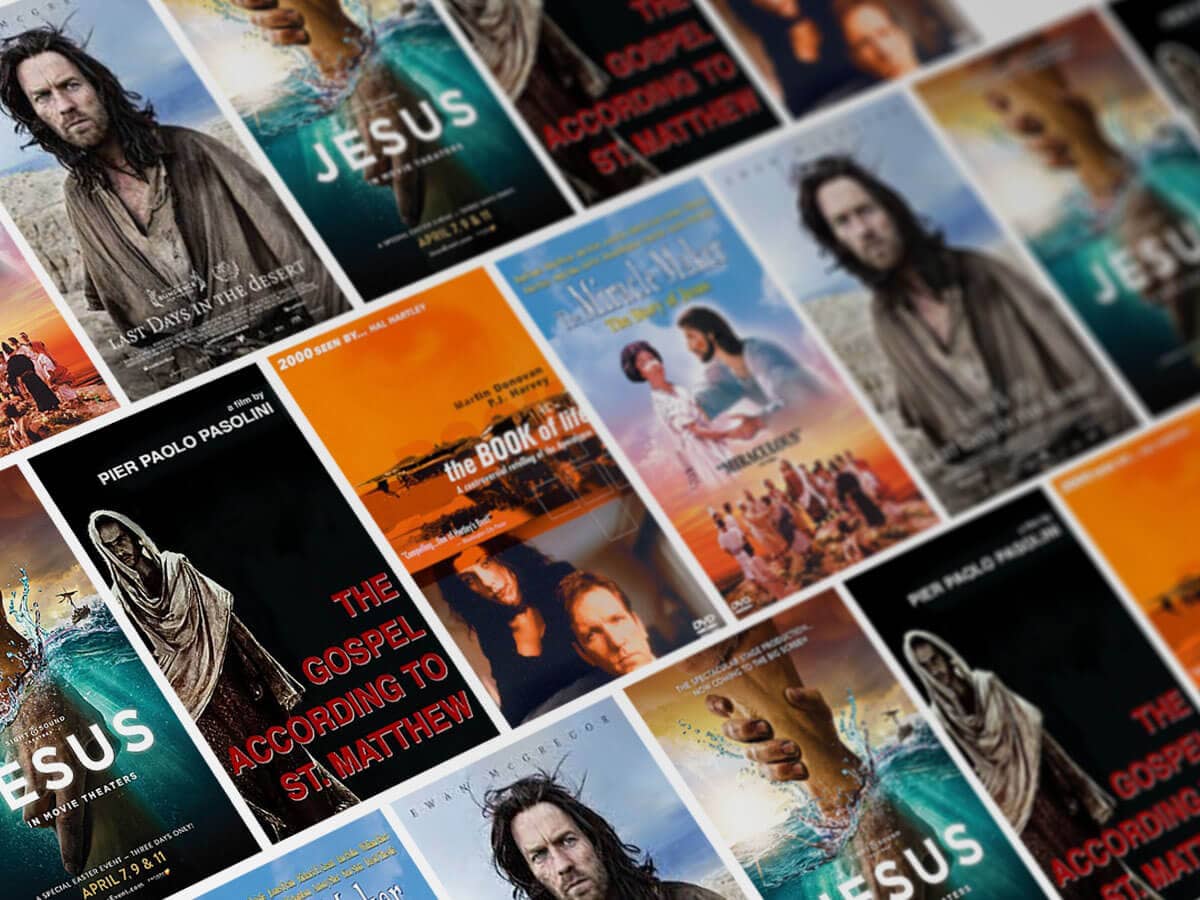

Since we could not deviate from the text, we ended up with a highly reliable and valid depiction of the Gospel, and a very different experience of it. Even people who know the Gospel well rarely read the whole story at once. On film, the story emerges much more strongly than in print or previous renditions. What comes through is the importance of each Gospel's individual witness. The New Testament gives us four Gospels for an important reason; each is part of the Christian mystery of Jesus' identity. When we finish the Gospel of Mark, many in the filmgoing public will see for the first time the radically different portraits of Jesus the evangelists create.

Once we left the scriptwriting stage, it was all we could do to keep up with the creative team's energy. One of our first concerns was how to suggest social differences by means of costume and behavior. Costume designer Debra Hanson showed us her experiments with dyeing linen and wool in natural colors. At one point we asked the set designers to rebuild a synagogue set that had been inadvertently built from a third century rather than first century model. (It originally contained an ark in the wall--not a feature of any first century synagogue that we know.) From script to the editing stage, our opinions were accommodated, though it sometimes cost a pretty penny to do so.

Musical director Steve Cera found suitable ancient instruments, locating skilled players to perform on them. Jeff Danna, a talented young composer experienced with ethnic instruments, composed an absolutely stunning and haunting score. The wedding at Cana, as a result has a really authentic feel to it, exotic without seeming strange, which depends greatly on the music. The miracle of the wine is accompanied by a miracle of sound.

While we were filming, we began to hear about the Mel Gibson project. From the early reports, a very clear distinction between the two projects emerged. He has interpreted a passion play; we made consensus decisions about how to depict the Gospel, rather than showcase our personal theories. One cannot be true to all of the Gospels at once. Ours is more about what one Gospel actually said, and less about how anyone, no matter how sincerely faithful, interprets the meaning of Jesus' life and death. If the film contains gratuitous violence or anti-Judaism that would be very troubling to me, considering the mission and ministry of Jesus and the meaning of his faith today.

The Gibson attempt at authenticity by using Aramaic and Latin is also misguided, a needless obfuscation. While Jesus surely spoke Aramaic, the Gospels are written in Greek; any Aramaic translation is going to be as far from the original as English. I doubt many Western actors can be good speakers of Aramaic, which contains many foreign sounds. But that remains to be seen. The Gospel of John, however, can be seen right now in some major cities and will be appearing soon in many more.

There are many achievements in "The Gospel of John" to be proud of. It captures, for one thing, the grandeur of ancient Jerusalem more authentically than previous films have done. The acting is superb. The relationship between Jesus and his disciples is intimate without beng cloying or sentimental. Philip Saville kept the camera in close on the scenes between the disciples and Jesus, giving the characters depth beyond other films of the life of Jesus. Henry Ian Cusick's Jesus has Shakespearean dimension. No other Gospel film has developed Jesus' humanity, while depicting his divinity as this one has. No other Gospel film has truly captured what Jesus meant when he said: "Love one another."