This article was originally published in 2003.

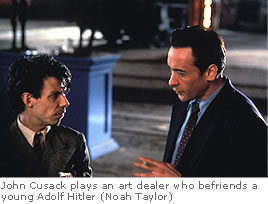

John Cusack's boy-next-door characters have, since the appearance of Lloyd Dobler in "Say Anything," had an obsessive side, usually brought out by the love of a young woman. In his new movie, "Max," Cusack plays the title role with the same urgency, but what's at stake is not the heart of a teenaged beauty, but the fate of civilization. An artist who lost his arm in the First World War, Max Rothman is determined to transform his world by fostering modern art as a gallery owner. The film shows how Max's hopes and life are powerfully determined by a struggling young artist he befriends named Adolph Hitler. Beliefnet talked to Cusack recently about his faith, his politics, and his new movie.

You were raised Catholic, but in your new movie you play Max Rothman, who is Jewish. How did you prepare for the role?

I was raised Catholic until I was old enough, you know, to say no. My father was great friends with [peace activist] Phil Berrigan, who just passed away. So obviously, I was informed by his kind of radical, left-wing, Jesuit mindset.

But growing up, the Irish, the Italians and the Jews, we all hung out together. Those groups seem to get it going pretty well. And research-wise, I did a little work. I read a book by a Yale professor Paul Mendes-Flohr, a history of the different manifestations of German Judaism. Some people saw themselves as Germanic, rather than Jewish, and some saw their identity as Jewish first and Germans second.

So Max is kind of like me: I was raised Irish Catholic but I don't consider myself Irish Catholic: I consider myself me, an American. Max probably didn't even think of himself as Jewish. He thought of himself as German. That was probably the only naïve thing about him.

Max has just returned from the First World War, and he seems lost. What is he looking for?

He captures that modern spirit you read about in "All Quiet on the Western Front." All these young men who went off with a very romantic vision of war came back totally shattered. It created this hungry, restless, wandering, kind of ghostlike energy. Max wants to recreate the 20th century. Everything his father taught him is wrong. Everything he learned is wrong. We all believed a certain way, he says, and look where it led us. We were in the trenches and we saw horses wearing gas masks. Whatever we did, it didn't work.

So many reasons. First of all, this notion that Hitler's only original idea was this fusion of art and politics. He saw that the future was going to be a fusion of these two forces. He despised the content of left-wing aesthetics, the art of the avant-garde, but the form he found remarkably powerful. He understood that, in the modern world, whoever controls images and symbols has the power. He understood that art reaches people's subconcious, and that battles will be fought on the spiritual plane of art for people's souls.

This is as relevant today. What was started then, we can never go back from. Look at the Taliban destroying those Buddhist statues -- destroying them not because there's buried treasure under there, but because the symbols have power. The reason bin Laden staggered the planes going into the towers was so every camera would be focused on the second tower when the plane hit. It was not only the murder, but the perpetual image of the horror that permeated into people's consciousness. It was not the murder itself, but the iconography of the murder. Somewhere on the Al-Jazeera network, someone chanting "blood Jew" to some frightening images. And right now the propaganda machine is gearing us up toward war. Every time I hear the "Showdown With Saddam" theme music, I get chills.

"Max" portrays Hitler as a struggling artist, just as he's taking up politics. The movie has caught some flak for humanizing Hitler.

That's exactly [the response] Hitler would have wanted. The best thing he could have imagined was to be some pan-Germanic mythological figure, instead of the liar and coward and thief that he was.

The movie portrays Hitler as a very recognizable, modern type.

He was so modern, in that he was obsessed with being famous. He was caught up with this modern rush to be have achieved greatness before turning 30. It's such a sad, modern kind of thing.

I think this is the century of both. [Max represents] the other world view, the one Hitler tried to kill. He's just a wonderful human: progressive, humanistic, compassionate, honest. He believes art has the power to transform the world. He gets back from the trenches and says, "Irony is for suckers." And he means it. He means it the way Phil Berrigan meant it. Berrigan killed people in World War Two and came back to earn his stripes in the anti-war crusade. Max has the same experience. It wasn't an abstraction.

There is a lot of talk in the movie about the art, both Hitler's and art in general.

Art is spiritual. Both Hitler and Max have come back from the war as damaged goods. Max uses art as a confessional, to deconstruct the imperialist war that led us to the trenches. Hitler wants to use his art to reinforce these romantic notions of war and to reconstruct the imperialist world to lead us to the next war. Max tells him, "You can be a modern artist, but you have to pay the price, and that's honesty. Can you be that voluptuous with yourself?" Well, Hitler obviously couldn't. Because then he would have to take ownership of his life. Max, on the other hand, is basically taking ownership of his life in the movie.

Even faced with Hitler's anti-semitism, Max calls it "kitsch," which is the worst sin he can imagine.

There's a wonderful book called "The Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age" by Modris Eksteins which defines kitsch as easy beauty without consequences, superficiality. But when applied to politics and taken to its extreme, he says, kitsch is the mask of death. Fascism was all aesthetics. There was no core principle to it. There was no truth to it. Even the idea of a master race, where was this blond, blue-eyed Aryan quality they talked of? They were all just creating it. When aesthetics become an end in themselves, you have kitsch, this sentimental vision with no ballast. Kitsch is more dangerous than it looks when taken to the extreme.

Do you think American politics today is kitsch?

It's all aesthetics. And even the people who are covering politics don't question whether that's right or not. They just tell you, "Bush is doing a wonderful job of convincing people he is compassionate." It's a very successful con job. We've stopped questioning that it's all theater. We all know it. It's just disgusting. One day Trent Lott says what he says about the South and lo and behold the next day President Bush is reading to multicolored children at the White House. It's just pure theater; it's kitsch.