By Joel Gunz

When we decided to visit the Spiritualist Church of Alice, I can’t speak for Amanda, but I was looking for one thing: a spooky thrill. That feeling of the uncanny is one of the oldest manufactured sensations known to mankind: even some 30,000-year-old cave paintings contain images that, in the right light (and with the right herbal assistance), must have looked to their ancient viewers as if they were coming eerily alive. That natural attraction to the uncanny found an apotheosis in the 19th century with the Spiritualist movement.

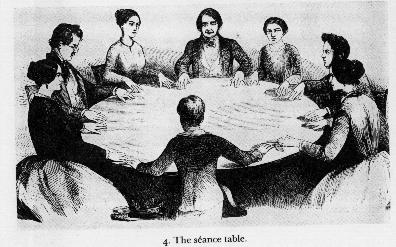

By the time World War I broke out, there were some eight million Spiritualists in the United States and Europe alone. From the beginning, the movement was dogged by accusations of fraud, quackery and opportunism. Still, millions — many of them otherwise rational people — flocked to séances seeking closure over their lost loved ones or maybe just seeking a thrill. Sigmund Freud was moved to comment on their motivations, suggesting in an essay on the uncanny that we modern thinkers “do not feel quite sure of our new [scientific] beliefs, and the old [animistic] ones still exist within us ready to seize upon any confirmation. As soon as something actually happens in our lives which seems to confirm the old, discarded beliefs we get a feeling of the uncanny; it is as though we were making a judgment something like this: ‘So the dead do live on and appear on the scene of their former activities!'”

The movement became so popular that during the 1920s, Scientific American magazine offered a $2500 cash prize to any medium who could successfully demonstrate supernatural abilities.

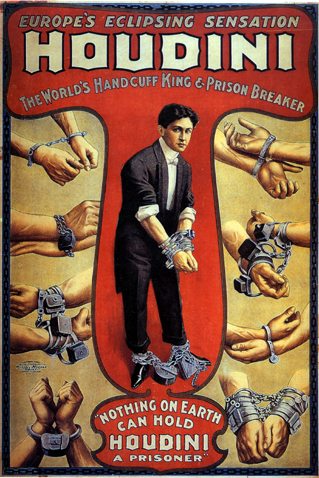

Enter Harry Houdini.

In addition to his famed skill as an escape artist, Houdini was also a professional magician. When his career had been at a low, he even hosted his own bogus séances, spooking attendees with floating tables and bugles that seemed to play by themselves. As his star rose, however, he left the practice behind. And then, along came another Spiritualist, Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, who hosted a series of meetings with prominent mediums in an effort to convert Houdini to Spiritualism. In each case, however, Houdini was able to expose their supposed contact with the dead as mere sleight-of-hand.

Doyle was so infuriated with Houdini’s “outing” of these mediums that he went public, announcing that the escape artist was actually using superior black magic to “block” these other mediums. Ironically, the author who created the literature’s greatest scientific detective refused to believe that which was before his very eyes. Sound familiar?

As Freud pointed out — and as I can personally attest — many of us still want to believe that spirits of the dead want to communicate with us. Before Houdini died, he told his wife, Bess, that if his spirit came back to visit her, he would utter the words “Rosabelle believe” as a code to prove that it was, indeed, him. Following his death, she maintained a lit a candle by his photo. After ten years of séances, her husband never appeared. Finally, she snuffed out the candle, saying, “ten years is long enough to wait for anybody.”

And regarding the Scientific American medium contest? The prize money went unclaimed.