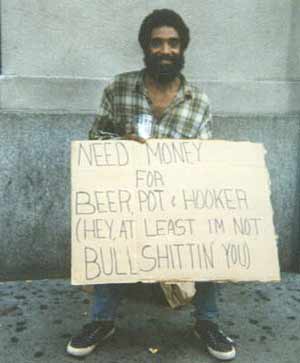

It’s not always this straightforward to tell where your money is going

by Lodro Rinzler

Before

Siddhartha Gautama attained enlightenment at age 35 he was a confused

twenty and thirty-something looking to learn how to live a spiritual

life. He had an overbearing dad, expectations for what he was supposed

to do with

his life, drinks were flowing, lutes were playing, and the women were

all about him. Some called him L.L. Cool S. I imagine close friends

just referred to him as Sid.

Many people look to Siddhartha as an example of someone who attained nirvana, a buddha. But here we look at a younger Sid as

a confused guy struggling with his daily life. What would he do as a

young person trying to find love, cheap drinks, and fun in a city like New York? How would he combine Buddhism and dating? We all make mistakes on our spiritual journey; here is where they’re discussed.

Each

week I’ll take on a new question and give some advice based on what I

think Sid, a confused guy working on his spiritual life in a world of

major distraction, would do. Because let’s face it, you and I are Sid.

Have a question for this weekly column? E-mail it here and Lodro will probably get to it!

—————————————————————————————————————————————

I live in a neighborhood where there a lot of homeless people. Each day I walk by and they ask me to help them. I don’t want to be cold-hearted but I also don’t want them spending money on alcohol or drugs. It’s hard to trust they will spend what I give them on food. Any advise?

—

A few years back Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche was on tour for his book Ruling Your World. During his New York City talk he spoke quite eloquently about compassion. At one point he spoke in depth about supporting people in their everyday endeavors. At that time something had been buzzing around my head for a while and I got up to ask him something.

“Rinpoche,” I said, “you’ve spoken a lot about how we can wish the best for someone but more often than not people are interested in a new car, or a new promotion, or ice cream. From a Buddhist perspective I understand that none of these things will really make them happy in the long run. Is it true compassion to support people in things that ultimately will break down, or lead to more desire to advance at work, or a stomach ache?”

The Sakyong paused for a minute and then responded by telling me that while these desires may not bring them ever-lasting happiness not everyone is going to see that right away. In fact, it’s not compassionate to highlight that. If I turned to my friend and said, “Nice new car. It’s going to break down someday and leave you stranded” they would think I am just being mean. The Sakyong said that on a very basic level it’s best to support other people in their happiness. Of course, dear commentors, on an ultimate level it’s best to lead everyone to perfect enlightenment (but seriously, take some time to enjoy your friend’s new ride).

All of this is a round-about explanation for how I have since related to the homeless in my neighborhood. I give semi-frequently and without judgment. If the person I make an offering to puts that money towards a night of shelter then that’s great. If he or she chooses to buy a beer instead then who am I to judge? I enjoy beer too.

It doesn’t strike me as fruitful to try to determine exactly what sort of person I’m giving to and how he’ll spend my money. I don’t know about you, but more often than not whatever estimation of character I come up with upon my first meeting with someone ultimately proves to be wrong. Instead of passing judgment, when someone asks me for money I look upon it as an opportunity to flex my generosity muscles.

I’m not the biggest gym nut (as is evidenced by my avoiding going to the Y right now by writing this post) but my understanding is that when lifting weights if we go just a little bit beyond what we feel comfortable with then that is when our muscles grow. We can think of our patience, discipline, generosity, and many other virtues in the same way. If we go just a little bit beyond what we feel comfortable giving to the Vietnam vet on the corner then we see our capacity for generosity begins to grow.

Our capacity for generosity is not limited to giving money but also includes offering our full presence when we talk with a co-worker, our time to someone who asks us for directions, or a friendly wink to someone who looks unhappy. The more generous we are the more we open our hearts to the world.

In this sense it is always good to give. When he became a buddha Sid was able to walk around and basically give the gift of the dharma to anyone he encountered. If you read enough stories of the Buddha you’d think that if you ran into him and he winked at you you would get enlightened. Unfortunately for you or me or our homeless friends we don’t have that effect on people (yet). And, before he was a Buddha, neither did Sid.

Let’s not forget that Sid himself was homeless after leaving the palace and relied upon the offerings of others, both before and after he attained enlightenment. I think if Sid were living and working in your neighborhood today he would return the favor by giving generously to his fellow human beings. He would do it wholeheartedly by engaging the individual, smiling at him, looking him in the eyes, saying a few kind words, and making an offering.

If you are uncomfortable offering money to people because you believe they will use it to harm themselves then you can buy food and offer it to them. The important thing, and I imagine Sid would agree, is that you acknowledge your homeless neighbors and treat them to as much generosity you can muster, even if that is just a smile.