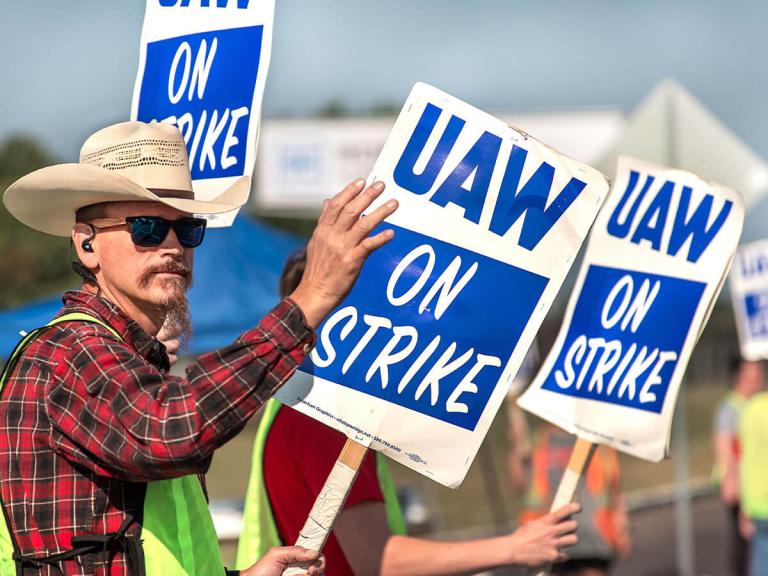

A CNN article recently pointed at the success of the United Auto Workers (UAW) strike against the automotive industry as pointing to a growing movement. The strike resulted in the biggest pay raise ever for workers at General Motors, Ford Motor Company, and Chrysler-owner Stellantis. CNN noted the unusual approach to the strike, with strike leader Shawn Fain sharing his Christian faith as he encouraged the workers. “Great acts of faith are seldom born out of calm calculation. It wasn’t logic that caused Moses to raise his staff on the bank of the Red Sea.,” he said. “It wasn’t common sense that caused Paul to abandon the law and embrace grace. And it wasn’t a confident committee that prayed in a small room in Jerusalem for Peter’s release from prison. It was a fearful, desperate band of believers that were backed into a corner.” Fain’s faith-filled speech is credited for mobilizing the workers.

CNN called it the marking of a revival of the social gospel movement in America. The social gospel movement began in the 1870s in America and traces its roots back to the Enlightenment. According to “Got Questions,” “Promoters of the social gospel sought to apply Christian principles to social problems, with a focus on labor reform. Other issues, such as poverty, nutrition and health, education, alcoholism, crime, and warfare, were also addressed as part of the social gospel.” While CNN treated Fain’s faith-based approach as a more recent phenomenon, most conservative Christians will recognize in the article details of a movement that sounds an awful lot like what is often called “progressive Christianity.” Progressive Christianity focuses on using the Gospel for cultural, economic, and social change.

Unlike House Speaker Mike Johnson’s faith, which has faced criticism as being a symptom of White Christian Nationalism, most proponents of the social gospel experience more favorable coverage, such as Dr. William Barber, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign. Barber calls Jesus a “a radical interruption [to the Roman powers-that-be]” and says that the Gospel should be used to transform systems to help the poor. Naturally, the idea of serving the poor and others is Biblical, coming from 1 John 3:16-18: “Hereby perceive we the love of God, because he laid down his life for us: and we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren. But whoso hath this world’s good, and seeth his brother have need, and shutteth up his bowels of compassion from him, how dwelleth the love of God in him? My little children, let us not love in word, neither in tongue; but in deed and in truth.”

Got Questions, however, does point to some issues with the Social Gospel movement. “However, as social needs were emphasized, the doctrines of sin, salvation, heaven and hell, and the future kingdom of God were downplayed. Theologically, the social gospel leaders were liberal and overwhelmingly postmillennialist, asserting that Christ’s second coming would not happen until humanity rid itself of social evils.” G3’s Josh Buice warned that while ministries helping others is noble, the main purpose of Christians is to spread the Gospel. “The mission of the Church of Jesus is to make disciples through the good news of Jesus among all peoples for their joy in Christ alone…You could start out with good intentions in a ministry in the local church, but over time, it could creep over into a social gospel that does little more than meet surface needs in your community.” The greatest concern for social gospel critics is the Enlightenment idea that humanity can progress to perfection. “Progress is an Enlightenment idea, grounded in the obvious and measurable progress of science but erroneously applied to the human condition,” writes Karen Swallow Prior in her book On Reading Well. “Although human manners and morals shift and change, and human cultures exchange one systemic sin for another, human nature does not change, let alone progress.”