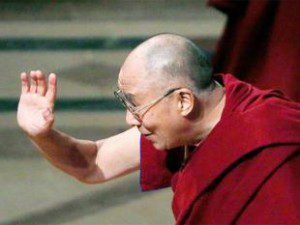

The Dalai Lama recently visited with President Obama. Not such an unusual event since they have visited before, but the Chinese Government used this as an opportunity to complain, threaten, and posture.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been through a lot. The Chinese occupied his homeland in 1949 and he went into exile in 1959. I won’t go into the politics of this issues or the death and destruction that has occurred, since these have been covered elsewhere (just Google it).

What I will comment upon is the value of a non-violent approach in dealing with conflict, adversity, and tragedy. A bitter, begrudging, and vengeful attitude would seem to be justified for the Dalai Lama in reference to China. But His Holiness has eschewed that approach in favor of compassion.

Why do the Chinese do what they do? Why does anyone do what they do? How can we understand the presence of violence, hate, and coercion in the world? It’s simple. People act destructively because they are in the grips of forces they cannot or choose not to control. Namely, these forces are greed or unrelenting desire, hatred or aversion, and confusion or delusion. When people are not in the grip of these forces, they enjoy generosity, love, and wisdom. Sounds potentially self-righteous, but I wonder if it’s not true.

The power-hungry would characterize this loving approach as weak. Fair enough. But I would tender the question as to whether there is more to this existence than power and control over material? I have no doubt that Mao Zedong got an intoxicating feeling from wielding power. Was he, however, happy? I speculate that he was not. Power breads pleasure but its fleeting nature is bound to bring anxiety too. Power reinforces that sense of “me” and “my” accomplishments.

If we embrace non-contingent love as the Dalai Lama does (and Buddhists and Buddha-inspired individuals all around the world), then the outer circumstances don’t matter. “I love you no matter what.” This doesn’t mean that His Holiness does not work towards political solutions for his people. He works. Yet, he works without attachment. Again, I speculate, but I think we have it on good authority that this is his attitude.

The Dalai Lama said in an interview in the Hindustan Times, “He (Chairman Mao) appears to me as a father and he himself considered me as a son. (We had) very good relations.” – See more at: http://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/mao-zedong-considered-me-as-his-son-dalai-lama/article1-878134.aspx#sthash.qWtSZHeZ.dpuf

Contrast this attitude to how we typically those who harm us. There is no plaintive narrative about how Mao ruined his life and wrecked his country. Instead, there is fond remembrance. Is this denial? Or is it wisdom?

What would we gain if we viewed the setbacks in our life within a fond frame of reference? Enmity, rumination, and complaint only foster negative feelings for the host, not the perpetrator. This is the wisdom of letting things be, of letting go into this moment. By letting go, the best action moving forward can be engaged because it is not being obstructed by attachments to the past.

There is freedom in relinquishing the narrative and dwelling in the present. We can learn a thing or two from His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He keeps pursuing his cause but he does not appear to be base his moment-by-moment happiness upon it.

Can we be agents of unattached change in the world too?