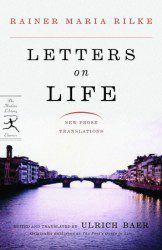

I am reading the lovely volume of excerpts from Rilke’s voluminous letters, Letters on Life, edited and translated by Ulrich Baer. Rilke wrote thousands of letters during his lifetime and seven thousand were reviewed for this volume.

I am reading the lovely volume of excerpts from Rilke’s voluminous letters, Letters on Life, edited and translated by Ulrich Baer. Rilke wrote thousands of letters during his lifetime and seven thousand were reviewed for this volume.

Rilke was a complex character. His biography, in some ways, parallels the Buddha’s. Like the Buddha he found the call of work in conflict with family life and he left his wife and child. They both did this around the same age — twenty-nine or so. The Buddha left to find the way beyond suffering and Rilke left to find solitude to write.

It is clear that Rilke understood the Buddha’s ideas. What is less clear is to what extent he was able to live them. I think this is the challenge we all face. It is one thing to understand the concept of impermanence (and even write about it) and quite another to live it as it unfolds moment by moment.

Here is a passage from a 25 November 1920 letter to Therese Mirbach-Geldern:

I have by now grown accustomed, to the degree that this humanly possible, to grasp everything that we may encounter according to its particular intensity without worrying much about how long it will last. Ultimately, this may be the best and most direct way of expecting the utmost of everything–even its duration. If we allow an encounter with a given thing to be shaped by this expectation that it may last, every such experience will be spoiled and falsified, and ultimately it will be prevented from unfolding its most proper and authentic potential and fertility. All the things that cannot be gained through our pleading can be given to us only as something unexpected, something extra: this is why I am yet again confirmed in my belief that often nothing seems to matter in life but the longest patience.

In this letter, Rilke is speaking of relinquishing what I call the agenda metaphor–our expectations for how things should go. The expectation warps the experience, and may, in fact, prevent its occurrence.

This is particular the case for experiences during meditation practice. If we aim for a particular state, we are sure to miss it. We can’t “plead” for bliss. If we can refrain from doing so, it may arrive as a “surprise.”

Since we are all works in progress, I agree with Rilke that patience is the utmost virtue. One moment after the next, returning to the present without frustration, reproach, or impatience. This is the path of mindfulness.

It’s not a quick fix. It’s not a gimmick. It’s a steady, subtle, and sometimes stealth way of transforming our experience from one infused with dissatisfaction to one infused with peace.