Those who dismiss the late James Dean as merely a brooding, self-absorbed young actor miss the point, I think.

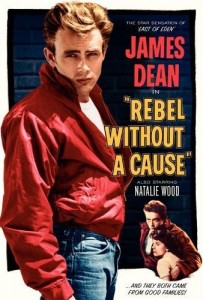

Dean, who evidently suffered both from the early loss of his mother and from abuse at the hands of a trusted clergyman, really was Jim Stark in many respects. The Nicholas Ray-directed film, “Rebel Without a Cause,” was the perfect vehicle for Dean to make a statement about American society in the 1950s.

One of the statements had wrapped inside it a more nuanced reality: American youth in the days of the American “space race” with the Soviets were caught in an existential “angst” that had been brewing on our shores since the late 19th century.

Enamored with the philosophy of naturalism as espoused by Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, and Herbert Spencer, American clergymen (incredibly!) like Henry Ward Beecher were bent on deconstructing the Bible.

Bizarre as this seems, it’s true. It left entire generations without a spiritual anchor, as they entered the shivering void without a belief in a Creator that cares for each of us, completely. And America’s determination to pass the Soviets in space exploration propelled even farther the notion that the universe is powered by the Impersonal Force.

Beecher in particular loathed the traditional Christian teaching that sin separates man from his Creator. In addition to preaching a completely new view of divine punishment — he denied its existence, as did Darwin — Beecher also embraced Spencer’s ideas on social Darwinism. That is, the precious few who are strong enough to advance society are superior to the rag-tag dregs of humanity, those who toiled so that the few could advance. This single line of thought drove such men as Andrew Carnegie, who symbolically shoveled the working masses into the furnaces of industry.

This view is diabolical, and diametrically opposed to the Gospel itself, which holds that the Shepherd (Christ) is completely committed to the well being of each of the sheep, that is, humanity. He will go anywhere and leave the 99 as it were, to retrieve the lost one.

Darwinism knows no such landscape. For the pure naturalist, random processes brought about everything. Nature simply moves along in unfeeling, unthinking fashion, allowing death and destruction (“nature is red in tooth and claw”) to steamroll the weak, paving the way for, in some sense, the advancement of the universe. No one knows of course what the ultimate end of such a landscape is; it might all burn out, or it might lurch along for eons.

Just as we cannot be sure of our origins, we more crucially cannot know where we are going.

And that is terrifying.

It was this basic framework of life, this narrative, that Jim Stark and his post-World War 2 band of rebels without a cause found themselves stumbling through.

Stark is angry with his parents. His mother and grandmother dominate the father (portrayed in excellent fashion by Jim Backus, later of Thurston Howell III fame in “Gilligan’s Island”). Watching Frank Stark bumble his way through life is painful, yet if that’s all we see, we miss the fact that he is simply a nice man who wants everyone to get along.

Jim needs more, though. Much more. He needs to know that someone is in charge, someone besides him.

We are all like that. When we put our feet on the floor each morning, if we believe that we are on our own, the tendency is to want to get back in bed and pull the covers over our faces. The world is too daunting to be met alone.

That, I believe, is the message behind “Rebel.” Stark, his 24-hour friend Plato, and girlfriend Judy each struggle with the absence of a healthy home life. They are, in effect, wandering in that cold void Carl Sagan was famous for intoning.

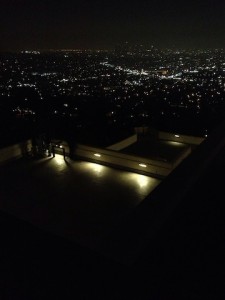

In fact, that one note calls to mind, for me, the most compelling scene in “Rebel.” Jammed into the planetarium at the iconic Griffith Observatory overlooking Hollywood, teens stare up at a dark mass filled with stars as a Dr. Minton (Ian Wolfe) warbles on an on about the fairly desperate environment each of us shivers in — that cold void of the universe. Here each of us suffers the ultimate terror of not mattering to an Impersonal Force that cares not whether we are ground up in death, or whether we sprint ahead of the other wretches for a few seconds in time, only to be of course swallowed up too by the specter of death.

One can see the palpable looks of fear and revulsion on the teens’ faces. They get it. They understand that if this version of reality is indeed true, then we are all lost. Muddling through only prolongs the suffering.

This is the net effect of Darwinian philosophy. And it is philosophy.

After the Scopes “Monkey Trial” of 1925, the grip of Darwinian philosophy began to assert itself over America. Bible-believing fundamentalists retreated into enclaves and left the spiritual successors of Beecher (such as Harry Emerson Fosdick) to spread what Francis Schaeffer would come to call a “Theology of Despair.”

This is what Jim Stark & Friends grappled with. Their parents did not have answers. Their teachers did not have answers. And they knew that they didn’t have answers. All sectors of society were contributing to the nihilistic worldview of history’s recent philosophers.

Dean reflected on all this during an interview before the film released:

“I think the one thing this picture shows that’s new is the psychological disproportion of the kids’ demands on the parents. Parents are often at fault, but the kids have some work to do, too.”

This was key, because Dean intuitively knew that each succeeding generation does not necessarily understand any more than previous generations. In our American culture today, especially among evangelical millennials, there is the feeling that yes, we have arrived at true understanding and have left behind our parents’ archaic Christian understandings of life.

James Dean’s “Jim Stark” was much more than a red jacket and white t-shirt. He was an observer of humanity, and for a brief moment, he showed us that if Dr. Minton’s view is the correct one — against the Bible’s portrayal of ultimate compassion and love from the Man from Nazareth — then all is indeed lost.

In point of fact, though, the Bible is defensible. Would that its guidelines for life and supernatural message had been taught to countless American youth these past hundred years. The Book tells us that we are all rebels, but the Creator wants us to bathe in the light of His love.

The New Testament writers believed that. They had simple faith, unlike the naturalism embraced by teachers who came much later. Paul, John, Peter & Friends preached a different reality.

A cause worth dying for.