When facing a movie like “The Ten Commandments: The Musical“–based on a recent stage production and set for DVD release this week–I always approach it from two angles: (1) Is the product a good/entertaining one?; and (2) Is it true to the text?

When facing a movie like “The Ten Commandments: The Musical“–based on a recent stage production and set for DVD release this week–I always approach it from two angles: (1) Is the product a good/entertaining one?; and (2) Is it true to the text?

The first good sign for this production is its enormously talented cast. The amazing Alisan Porter plays Miriam (you can also catch her in the Broadway revival of “A Chorus Line”); Aharon Ipale stars for his second time as the Pharaoh Seti (first time was in”The Mummy”). Michelle Pereira (“Yokebed,” Moses’ mother, or as I was taught to pronounce it, Yokheved) and Kevin Earley (Ramses) also turn in passionate performances. Some voices are so phenomenal that they can even make cheesy lyrics (Joshua, a slave, rebels with “you can’t tie a rock to my soul”) forgivable.

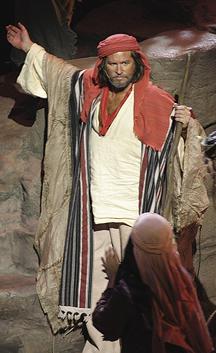

I admit, I snickered when I read the words “Val Kilmer IS Moses in ‘The Ten Commandments.'” But the truth is that Kilmer wasn’t all that bad–perhaps because he’s played Moses once before (in 1998, for Dreamworks’ “Prince of Egypt”). Kilmer does a lot of the “talky singing” that’s usually assigned to characters tasked with major plot exposition, wherein each musical phrase is packed with more words than human lung capacity should be able to handle. Thankfully, “Top Gun’s” Iceman is not expected to perform complicated musical arrangements and choreography.

But the production suffers because its heart, its Moses, mostly reacts to the musical going on around him. The quality of his voice is certainly not at the same level as the highly trained cast that surrounds him, but it was fine. But is ‘fine’ enough for a musical? I mean, I have a fine voice, but I’m not auditioning for Broadway shows where the marquee would boast: “‘Queen Esther: The Musical’ featuring Celine Dion, Mariah Carey, Kelly Clarkson, Josh Groban, and Esther Kustanowitz.”

Textual accuracy is more complicated. Bible stories represent the bedrock of contemporary Judeo-Christian faith; and biblical purists will just have to make some spiritual concessions when watching this musical. The dramatized story, both in the DeMille epic and here, tacks on a love triangle (Ramses is to marry a woman who’s in love with Moses; she sings about it in “A Love that Never Was.”) The brotherhood storyline is also a major hook for promotion: “Two men. Raised as brothers. Divided by history.”

But the story has never needed this Hollywood touch, nor does it need a post-Red Sea crossing reconciliation between the brothers, who proclaim their love forever. Pharaoh even proclaims, “Moses, your God is God.” (Never happened in the Bible.)

When Moses is banished after slaying the Egyptian taskmaster, the entire cast drifts into a musical number, one at a time, wondering “What about us, what will we be without him?” While, this is a very effective song of loss, it’s not terribly biblical. Similarly, I watched the plague sequence three times, and I’m not sure all 10 are included. Some story elements that are not in the straight text in Exodus do exist in biblical legend–for instance, the possibility that Bithia/Batya, the daughter of Pharaoh who draws the infant Moses from the water, exited Egypt with the Hebrew slaves and was present at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah. On the other hand, I doubt any of the Midianites, Moses’ in-laws, were Asian or blonde, which may make me a racist, a biblical Purist, or both.

Were Egyptian slaves really dressed so scantily? With wardrobe by BCBG Max Azria, never has slavery looked so abtastic. With all those exposed midriffs, it’s no wonder that when the Children of Israel engage in nostalgic yearning for the Egypt they’d left behind (“Where is the land of milk and honey?”), their primal moan quickly enables the sheer libido of the people to physically manifest as a golden calf.

There will be those who decide, after hearing a voice of God that sounds not wholly unlike a vocoder-infused staccato rap, to call it a day. But then again, the music successfully highlights how remarkably layered the Exodus story is, both in terms of the human pathos involved and the faith themes. Moses is not just a man threatening the economic system of Egypt by trying to free its slaves, he was raised in the Egyptian palace as the son of Pharaoh’s daughter, which ups the stakes. Whether or not the actual story sets up Pharaoh and Moses as literal brothers, the story is still about freedom and about the men who represent Gods.

Plus, Val Kilmer in a tallit (prayer shawl)? To a Jewish girl with “Top Gun” memories, that’s totally hot.