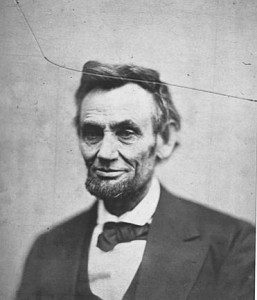

The recent release of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln, which opens with a dramatization of one of Abraham Lincoln’s dreams, may have helped to remind us that in an earlier America, dreams were widely respected and shared. People – including those in very high positions – actually paid far more attention to dreams in Lincoln’s time than they admit to doing today.

The recent release of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln, which opens with a dramatization of one of Abraham Lincoln’s dreams, may have helped to remind us that in an earlier America, dreams were widely respected and shared. People – including those in very high positions – actually paid far more attention to dreams in Lincoln’s time than they admit to doing today.

I raised the question in my last article here: Could Lincoln have escaped assassination had he know how to get clearer information from his premonitory dream, and how to take action to avoid the evil future it portended? The problem, in Lincoln’s era, was not that people lacked respect for dreams, but that they frequently lacked a clear and effective process for harvesting guidance for dreams and and taking appropriate dream-guided action – the process we now offer through Active Dreaming.

My friend Wanda Burch, who is both an historian, a gifted and prolific dreamer, and a teacher of Active Dreaming, has been engaged for several years in a deep study of dreams in the era of the American Civil War. Her work helps us to understand the extent to which the America of Lincoln’s era was still, in many ways, a dreaming society, and how dreams were a secret (or not so secret) engine in many lives, of the great and the obscure.

Wanda contributed a previous guest blog on the dreams of a Georgia woman, Sara Wadley. Fascinated by Wanda’s recent discoveries in the dream diary kept by a young Louisiana woman named Sarah Morgan from 1862-1865, I invited Wanda to contribute a second guest article.

“I would not care to sleep, if I could not dream”

guest blog by Wanda Burch

In 1862, Sarah Dawson Morgan, age 20, a wealthy young woman from Baton Rouge thought she had already lost everything – the unforeseen death of her father, Thomas Morgan, preceded by the death of her beloved brother, Henry, in a duel. Then the American Civil War brought physical destruction to her doorstep, first in Charleston, then in Baton Rouge, where her family’s house and possessions were destroyed.

Sarah Morgan began a diary, recording her frustration, anxieties, hopes, and her dreams. She dreamed of “rifle shells and battles”while she tried to knit together the threads of her torn life and face her present, in preparation for whatever the future might hold. Sarah moved – with her mother and sisters – from Baton Rouge to Linwood, the plantation of a family friend, back again to occupied Charleston, recording headings of houses and plantationsthat allowed refuge in a vast network of friendships and family. Sarah looked on a burned southern landscape with hope from her dreaming:

“Miriam and mother are going to Baton Rouge in a few hours, to see if anything can be saved from the general wreck. From the reports of the removal of the Penitentiary machinery, State Library, Washington Statue, etc., we presume that that part of the town yet standing is to be burnt like the rest. I think, though, that mother has delayed too long. However, I dreamed last night that we had saved a great deal, in trunks; and my dreams sometimes come true.”

The house was totally destroyed, paintings ripped from their frames and slashed repeatedly; dresses and textiles ripped to shreds; furniture broken and burned; books ripped and burned; china smashed, busts of Diana and Apollo abused, but at the end, as in the dream: “Forgot to say… Miriam recovered my guitar from the Asylum, our large trunk and father’s papers (untouched) from Dr. Enders’s, and with her piano, the two portraits, a few mattresses…and father’s law books, carried them out of town. For which I say in all humility, Blessed be God who has spared us so much.”

Dreams poured through her diary, pleasant dreams, confusing dreams, touching dreams of visits with family and friends. In a resounding statement of affirmation of dreaming, she wrote that she would not forego her dreams for any inducement. In her dreams she could visit heaven or a fairy land. She could go flying on white wings or float on clouds where she looked down on the moving world “or I have the power to raise myself in the air without wings and silently float wherever I will.”

She heard Paul preach to the people, visited strange lands and great cities, talked with people she had never met, including spending a week with Charlotte Bronte hearing details of her “sad life.” Shakespeare discussed his work in her dreams, revealing characters and sharing she had the “tenderest heart” he had ever “sung.”

More thoughtful, Sarah notes, “I see father and Harry in dreams. Once I walked with Hal through a garden of Paradise. Fountains, statues, flowers surrounded us, as we wandered hand in hand. We stopped before a statue that held a finger to its lips, when he said “Did you ever see Fitch’s celebrated picture of Eternity? No? Well let me show it to you. Nothing but that picture can give you an idea of the vastness of this eternity. Come!” Sarah followed until they arrived at an immense crystal wall where she saw moving figures she could not define. Fascinated, she wrote passionately that she watched these “otherside” figures, knowing they were real and always moving, above all of them hovering “a Something,” too mysterious for her comprehension: “ Dreams! Who would give up the blessing? I would not care to sleep, if I could not dream.”

Sarah recorded that the servants believed she spoke to the spirits because she talked to them. She admitted to her journal, if not to the servants, that “every morning and evening I walked to the graveyard with a basket of flowers, and would sit by father’s and Harry’s graves and call their spirits to me; and they would all fly to me, and talk and sing with me for hours until I would tell them good-bye and go home, when they would go away too.”

In a sweet final dream of her brother Sarah dreamed [Dec. 25, 1863] she was sitting by Hal’s grave, “only that he was buried in the earth, instead of that close vault; and that as I plucked the weeds that covered it, gradually I unburied him. O how distinctly I saw him! I dreamed he opened his eyes.” He told Sarah he was lonely and asked her to hold him. She held him and rubbed his wounds until he was warm. She wept that she could not warm life back into his body; but he did not want her to stay. He asked her to lay him down, watch him sleep and then leave him to rest. Sadly she complied.

She loved her “royal purple” dreams where romance survived when family were dying and the land outside was torn and bleeding. She dreamed of marriage, once with someone she did not care for, waking in a torrent of emotions, begging the opportunity to change such a dream. With the dream help of her sister, she escaped the marriage: “A tame ending, but my horror at the thought of marrying that man has not yet deserted me. I am glad I did not, even in my dreams.”Awarded with another romantic dream, she saw a marriage with a foreigner, swearing that if the dream meant he was a Federal soldier she would still follow her heart and marry him. Sarah married an Englishman, Frank Dawson, in 1874, more than ten years beyond that entry.

From Linwood Plantation, she wrote she was not conscious of being “alive until I awake abruptly in the early morning, with a confused sense of having dreamed something very pleasant.”

In a possibly prophetic dream of the destruction of the South, terror replaced delight. On July 27, 1863, Sarah awoke sick, trembling, apprehensive, unhappy, and every thing in a breath. Trouble will follow, I feel. O my prophetic soul! I do believe in dreams!” Sarah noted that “as usual” she named the bedposts, a habit she adopted to remember her dreams. She dreamed of three letters, one from a man familiar to her, Col. Steadman; and then she saw herself speaking to a Yankee officer who described the loss of their possessions.

In a horrible ending, she saw herself carrying a baby that grew larger and heavier, finally turning into a great bloody ball that burst. She awoke saying aloud: “Bless that baby; my unfailing prophecy of trouble!” The smaller details of her prophetic dream unfolded the next day when her sister held out to her three letters, one from Col. Steadman; and additional circumstances placed her in contact with the Union officer in charge of Confederate prisoners known to her. She did not understand the bloody baby but felt it was a dreadful prophecy. Still believing the South would find its way to victory, she never admitted that her dream of a bloody baby might foretell the end of a way of life that she had known in her childhood.

Her final diary entry, on June 15, 1865, admits the sad end of her beloved South, as she knew it, and what she could not face in that disturbing dream: “Our Confederacy has gone with one crash—the report of the pistol fired at Lincoln.”

(c) Wanda Burch. All rights reserved.

Quotations from Sarah Morgan, The Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman, edited by Charles East (Athens, Georgia; University of Georgia Press, 1991).

Wanda Burch is helping us to construct a missing chapter in the history of American dreaming, a dimension of human experience rarely taught in our schools and colleges. She.is the author of She Who Dreams and a forthcoming study of dreams during the American Civil War. She is a certified teacher of Active Dreaning who leads Active Dreaming workshops and healing retreats for veterans. Visit her website