Looking over old journals as I cull experiential material for a new book, I am reminded just how many of my big experiences of inner and other worlds have taken place in a liminal state of consciousness, on the cusp between sleep and waking. We have all been there, though often we rush through it too fast. Spending more time in the twilight zone between sleep and waking is the easiest way to become a conscious or lucid dreamer. It is a space where creative connections are made, and has been the source of so many breakthroughs in science and literature that in my Secret History of Dreaming I call it “the solution state”.

Looking over old journals as I cull experiential material for a new book, I am reminded just how many of my big experiences of inner and other worlds have taken place in a liminal state of consciousness, on the cusp between sleep and waking. We have all been there, though often we rush through it too fast. Spending more time in the twilight zone between sleep and waking is the easiest way to become a conscious or lucid dreamer. It is a space where creative connections are made, and has been the source of so many breakthroughs in science and literature that in my Secret History of Dreaming I call it “the solution state”.

Active dreamers tend to spend a lot of time in the twilight zone, even whole nights. In everyday life, the easiest way to embark on conscious dream journeys is to practice maintaining full awareness as dream images rise and fall during twilight states. The twilight zone offers optimum conditions to develop your ability to make intentional journeys beyond the physical body to learn the nature and conditions of other orders of reality.

In the language of the sleep scientists, the twilight zone is the realm of hypnagogic and hypnopompic experiences. Hypnagogic literally means “leading toward sleep”; hypnopompic means “leading away from sleep.” But these terms do not take us to the heart of the matter. You may enter the twilight zone before and after sleep, but you may also enter it wide awake, with no intention of sleeping. It is not the relationship to sleep that defines the twilight zone; it is its character as a border county. It is the junction between sleep and waking, certainly. But more than this, as Mary Watkins writes beautifully, it is “the plane of coexistence of the two worlds.”

In this borderland, you will find the gates to other worlds opening smoothly and fluidly — if you let them and are prepared for what may follow. When I allow myself to drift through this frontier region with no fixed agenda, I have the sense of leaning through a window or a doorway in space. Sometimes this feels like hanging out of the open hatch of an airplane. I have come to recognize this as the opening of a dreamgate. Depending on circumstances and intention, I can step forward into the next dimension or haul myself back into physical focus.

From this departure lobby, the great explorers of the imaginal realm have used many gates and flight paths. This is why the twilight state has such vital significance in dream yoga, in shamanic training, in the Western Mystery traditions, in the “science if mirrors” of the medieval Persian philosophers, and in other schools of active spirituality.

According to Tantric teachings, it is by learning to prolong this “intermediate state” and to operate with full awareness within it that you achieve dream mastery and, beyond this, the highest level of consciousness attainable for an embodied human. The Spandakarika of Vasagupta, which dates from the tenth century, recommends the use of breathing exercises to focus and maintain awareness as you move from waking into the twilight state. The dreamer is urged to place himself “at the junction between inhaled and exhaled breaths, at the very point where he enters into contact with energy in the pure state.” This is the entry into conscious dreaming, whose gifts (according to Tantric text) could be immense: “The Lord of necessity grants him during dreams the ends he pursues, providing that he is profoundly contemplative and places himself at the junction between waking and sleeping.”

The aim of the practice is to achieve continuity of consciousness through sleeping, waking, and the intermediate state. When this is attained, the practitioner has ascended to the mystical Fourth State — the turiya of the Upanishads. This is the highly evolved consciousness of a person who has awakened to the reality of the Self; it now infuses his awareness at all times.

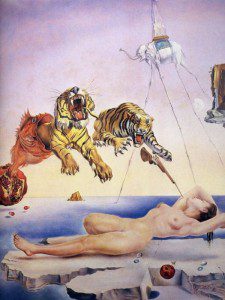

Salvador Dali, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranata

Adapted from Dreamgates: Exploring the Worlds of Soul, Imagination and Life After Death by Robert Moss. Published by New World Library

Adapted from Dreamgates: Exploring the Worlds of Soul, Imagination and Life After Death by Robert Moss. Published by New World Library