One of the classic accounts of how shamans are called to their practice by dreams comes from Isaac Tens, a Gitskan halaait (shaman) in the Pacific Northwest. The French Canadian scholar Marius Barbeau recorded his narrative and his songs at Hazelton, British Columbia, in 1920. This is a fierce story, in which dreams spill over into the physical world and birds and animals behave like spirits (as shamans know them to be).

One of the classic accounts of how shamans are called to their practice by dreams comes from Isaac Tens, a Gitskan halaait (shaman) in the Pacific Northwest. The French Canadian scholar Marius Barbeau recorded his narrative and his songs at Hazelton, British Columbia, in 1920. This is a fierce story, in which dreams spill over into the physical world and birds and animals behave like spirits (as shamans know them to be).

“Thirty years after my birth,” as Tens tells it, he was chopping firewood at dusk when a huge owl flew at him. “The owl took hold of me, caught my face, and tried to lift me up.” Tens lost consciousness. When he came round, he found he had fallen into the snow, and blood was streaming from his mouth. His world became stranger. As he dragged himself home, the trees seemed to lean over him, and then slither after him like snakes. In bed, he fell into a chaotic state. He felt he had fallen into a whirlpool.

His family brought in two shamans, who recognized a possible calling in this spiritual emergency. They told Isaac Tens he was meant to become a shaman like them. He did not want to hear this. He recovered, and went hunting. After killing and skinning a couple of fishers, he saw another huge owl. He shot it and saw it fall. But when he went to recover the body, there was no trace of the owl. Returning to his cabin, he had the impression of a crowd of spirits, pursuing him. He fell down in trance, in the snow.

When he was able to make his way home, over a frozen river, his flesh seemed to be boiling, and a song burst from him. “A chant was coming out of me without my being able to do anything to stop it.” Around him, visible only to him, he saw spirit animals. “Such visions happen when a man is about to become a halaait. The songs force themselves out complete, without any attempt to compose them.”

The shaman-songs continued to stream from him. He now accepted his calling. To learn his trade, he was advised to live in seclusion, seeing only four cousins, fellow-members of the Wolf Clan, who watched over him. The key element in this period of training and preparation was dreaming. “I had to have dreams in order to act.”

Established medicine men shared their craft with him, when he proceeded to work with his own patients, but Tens’ primary guidance came from dreams and visions. “I began to diagnose the cases by dreaming.” His dreams showed him the right songs and charms and animal spirits to use in a particular case. To extract an ailment – or more exactly, the evil spirit that had carried an illness into a patient’s body – he would place a “charm” over himself and then extend it to reach or cover the patient. The charm “was never an actual object, but one that had appeared in a dream.”

Tens acquired a spirit canoe that he used in healing through a powerful dream. “In a dream I once had over the hills, I saw a canoe. Many times it appeared to me in my dreams. The canoe was sometimes floating on the water, sometimes on the clouds. When any trouble occurred anywhere, I was able to see my canoe in visions.”

He eventually gathered 23 songs on power and healing, mostly delivered directly to him through dreams and visions. He dreamed a song of the Salmon.

The village will be healed when my Salmon spirit floats in

He dreamed that his two deceased uncles gave him rattles for each hand, and that a Grizzly Bear ran through the house and then soared up into the sky, among the clouds. He chanted the sounds of the Bear making thunder in the Earth, then flying up, while shaking a rattle with each hand.

In a vision, he traveled in a strange country, full of bees. The bees stung him all over his body. Then an ancient woman helped him to grow. He sang:

Beehives were shooting my body

Grandmother makes me grow

in my vision. Eyiwaw!

In another vision, he fell from a great height into a canoe that carried him up between the peaks of the mountains, where he heard the mountain spirits talking to each other in voices like bells. He sang:

The mountains are talking to each other

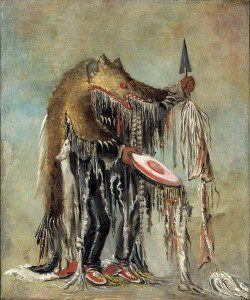

In treating the most serious cases, Isaac Tens would dress in a bearskin robe with a bear claw headdress, assuming the power of the greatest medicine animal of North America, whose song he carried through his own dreaming. On such occasions, family, friends and fellow-shamans would be called together to create a healing community.

Soul retrieval was often the order of business. “If the patient is very weak,” the shaman “captures his spirit into his hands and blows quietly on it to give it more breath. If weaker still, the halaait takes a hot stone from the fireplace and holds the spirit over it. Perhaps a little fat is put on the hot stone to melt. The hands turn from one side to the other, thus feeding the sick spirit.” Finally, the spirit is transferred to the patient’s head.

~

Quotations are from Marius Barbeau, Medicine Men of the Pacific Coast. Bulletin 152, National Museum of Man, Ottawa, 1958. Versions of Isaac Tens’ songs here are my own, based on Barbeau’s translations.