The heartfelt responses to my post on the healing gifts of the Deer lead me to talk today about how the power of this living symbol brought outer and inner events together in a magical way.

Several years ago, I immersed myself in a study of symbol of the antlered deer in myth and religion. I found, as I reported yesterday, that in many ancient and indigenous traditions, the antlers are a symbol of spiritual authority because they grow above the physical head, reaching towards the realm of spirit. They signify regeneration, because they die and grow back, bigger than before. They are worn by Cernunnos, the ancient Celtic Master of the Animals, by Mongol women shamans, and by the rotiyaner or “men of good minds”, the traditional chiefs of the Six Nations of the Longhouse, or Iroquois. Visually, deer antlers suggest the shape of a tree, even the World Tree that shamans climb; the resemblance is in the French word for antlers, which are called thebois – wood – of the deer. There is a mystical connection between the deer, especially the flying deer (cerf volant) and the early kings of France.

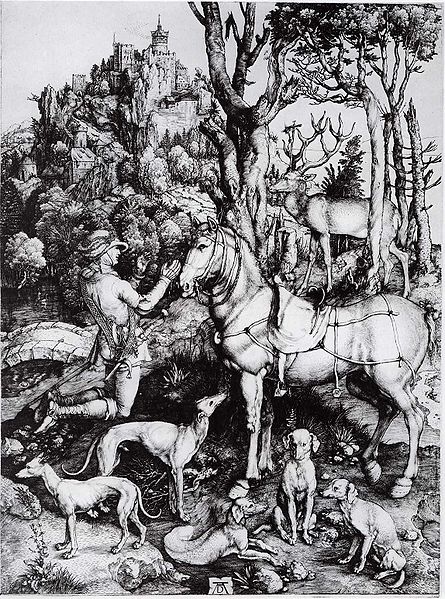

Studying religious iconography in France in 2005, I became fascinated by the moment in the history of the Western imagination when the old pagan image of the Antlered One fused with that of the Christ. You can view the results on the facade of the great Gothic church of St-Eustache at Les Halles, once the site of the famous market. Look up and near the top, lording it over the gargoyles, you’ll find the figure of an antlered stag with the Calvary cross between his antlers. According to legend, St. Eustace (to give him the Anglo version of his name) was formerly a pagan Roman general named Placidus, who reveled in the hunt until one day he confronted a magnificent stag through whose deep eyes the Christ light shone. Christ spoke to him through the deer. The general gave up hunting and converted to the new religion. This moment of conversion through the agency of the deer has been memorialized in numerous painted and woven and sculpted images, including a marvelous 15th century painting by Pisanello that I viewed in the National Gallery in London and the 1501 engraving by Albrecht Dürer shown here.

The St.Eustace legend may be an invention, designed to claim the lustre of a commanding symbol of the old ways for the new religion, just as churches were placed on the sacred sites where pre-Christian rituals were celebrated. However, the theme of the power of the deer spirit to tame the killer in man resonated with me deeply, because on a mountain in the Adirondack mountains of New York, I had heard a similar tale from mountain men who knew nothing of Placidus or Eustace: that three hunters, on separate occasions, had come face to face with a great stag in that wild terrain, and that each time, something in the deep, steady eyes of the deer had persuaded the hunter to lay down his rifle and go home.

Not long after that trip to France, I was talking about the theme of Christ in the Stag on my cell phone, while walking my dog in a park in upstate New York that is notably clean. As I described the stag with the cross between his antlers on the church at Les Halles, I glanced down and saw an orange cardboard disk at my feet. It bore the image of a stag with a Calvary cross shining between his antlers. This was one of those moments when the universe gets personal. I knew that in that moment, the symbol that was blazing in my mind was shining back at me, on the grass at my feet.

I put the cardboard disk in my wallet and have carried it ever since, a token from the world. I did not identify the source of this version of the stag with the cross until, on my way to give a talk at a bookshop in Vancouver B.C. some months later, I stopped at an Irish pub across the street. I needed to use what Canadians call the washroom, and as I did what boys do, I saw the image from the cardboard disk in front of my nose, in a framed poster for Jägermeister, a herbal liqueur whose name means “hunt-master” and (I later learned from my youngest daughter) is a favorite on college campuses with kinds who want to get “hammered.”

Jung noted in his foreword to his most important work on synchronicity that “my researches into the history of symbols… brought the problem [of explaining synchronicity] ever closer to me” His experiences of symbols irrupting into the physical world led him to sympathize with Goethe’s magical view “We all have certain electric and magnetic powers within us and ourselves exercise an attractive and repelling force, according as we come into touch with something like or unlike.” I learned from the Deer that such powers are magnified when our minds and our environment are charged with the energy of a living symbol. In a chapter on “Symbol Magnets” in my new book Active Dreaming I discuss the broader play of this kind of magnetism.