When we give the best of ourselves to a creative project – accepting the risks that creativity involves – we draw the interest and engagement of supporting intelligences from beyond our ordinary field of connection. There is a passage in Yeats’s essay Per Amica Silentia Lunae (“The Friendly Silence of the Moon” , included in his book Mythologies) that may explain how we can develop a co-creative relationship with minds operating in other times or other dimensions. When Yeats refers (in the first line below) to “fellow-scholars” he is not thinking about people of his own time, but minds that are working and reaching out from beyond time and space:

I had fellow-scholars, and now it was I and now they who made some discovery. Before the mind’s eye, whether in sleep or waking, came images that one was to discover presently in some book one had never read, and after looking in vain for explanation to the current theory of forgotten personal memory, I came to believe in a Great Memory passing on from generation to generation. But that was not enough, for these images showed intention and choice. They had a relation to what one knew and yet were an extension of one’s knowledge. If no mind was there, why should I suddenly come upon salt and antimony, upon the liquefaction of gold, as they were understood by the alchemists, or upon some detail of cabbalistic symbolism verified at last by a learned scholar from his never-published manuscripts, and who can have put it together so ingeniously?…The thought was again and again before me that this study had created a contact or mingling with minds who had followed a like study in some other age, and that these minds still saw and thought and chose.

When I was writing my Dreamer’s Book of the Dead I often felt the intimate presence of a personality that seemed to be connected with Yeats, and a play of energy and circumstance that was best explained by the notion of a mingling of minds of the kind he described. I also felt – then and in the midst of similarly consuming creative projects – the force of that goading and guiding energetic self that Yeats called the daimon, usually with a capital D.

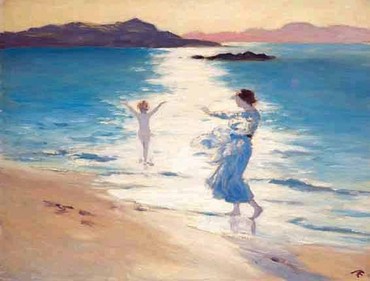

When the daimon is engaged, I can work round the clock without fatigue, to find after an all-nighter that there is a great ship’s engine thrumming away, somewhere deep in my being, driving the vessel across wide waters. There is the sense of a larger entity that does not permit the ordinary self to slumber when great things are afoot.

Yeats approached the idea of the daimon again and again in his work, and it means different things in different writings. At one point, he used the word “daimon” to describe something like Jung’s shadow, as a composite of characteristics most antithetical to the personality, as an energy drawn to its opposite. Sometimes he used the term to mean “spirit” or “spirit of the dead” as the ancients did, and practiced techniques – inside the Golden Dawn and improvised in his own experiments – for evoking and contacting these spirits. He also seized on the idea (from Heraclitus) that the daimon is the bearer of a personal destiny, with what man is often at odds and yet at the same time at odds.

The Greeks, a certain scholar has told me, considered that myths are the activities of the Daimons, and that the Daimons shape our characters and our lives. I have often had the fancy that there is some one myth for every man, which, if we but knew it, would make us understand all he did and thought

The Yeatsian daimon I understand best is the one he evokes in these words from Per Amica Silentia Lunae:

When I think of life as a struggle with the Daimon who would ever set us to the hardest work among those not impossible, I understand why there is a deep enmity between a man and his destiny, and why a man loves nothing but his destiny.

When we are passionately engaged in a creative venture – love, art or something else that is really worthwhile – we draw support from other minds and other beings, seen and unseen. – According to the direction of our will and desire, and the depth of our work, those minds may include masters from other times and other beings.

We draw greater support the greater the challenges involved in our venture. Great spirits love great challenges. Whether we are aware of it or not, all our life choices are witnessed by the larger self. The daimon lends or withholds its immense energy from our lives according to whether we choose the big agenda or the little one. The daimon is bored by our everyday vacillations and compromises and detests us when we choose against the grand passion and the Life Work, the soul’s purpose. – The daimon loves us best when we choose to attempt “the hardest thing among those not impossible.”

Adapted from The Dreamer’s Book of the Dead by Robert Moss (Destiny Books)