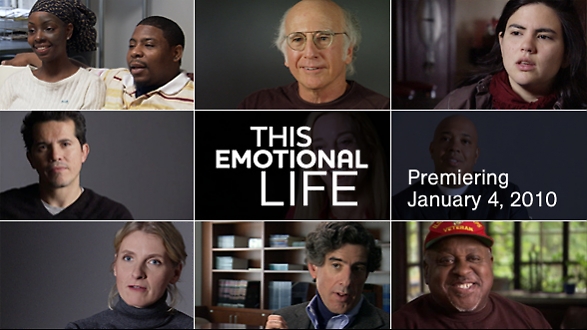

Harvard psychologist and bestselling author Daniel Gilbert has teamed up with Vulcan Productions and the NOVA/WGBH Science Unit to create a multimedia project called “This Emotional Life.” A 3-part documentary premieres on PBS January 4-6, 2010, but there is plenty going on already on the fascinating website, which features expert bloggers and clips from the series.

Featured in the second episode is Robert Antonioni, a state senator in Massachusetts who faced up to his own depression after the suicide of his brother. His personal experience has strengthened his own position as a key policymaker in Massachusetts. I had the opportunity to interview him.

Question: How did the suicide of your brother strengthen your position as a key policymaker in Massachusetts?

Robert Antonioni: I gradually came to realize, following my brother’s death, that I was in a unique position to bring about positive change concerning suicide, simply by being a member of the state Senate. But first, I had to address the feelings of grief, guilt over my “neglect” of my brother’s struggle, and confront my own longstanding battle with depression.

Immediately following my brother’s passing, I was filled with remorse and guilt, that I had neglected John in some fashion. I considered leaving the Senate, believing that I did not deserve to belong given my neglect of my brother, and my feelings of guilt.

I decided to go into counseling to help cope with these feelings. It was through constant weekly sessions with my therapist, and the eventual use of antidepressants, that I came to recognize that I was not responsible for John’s death. My healing came slowly, not noticeable on a daily basis, but recognizable over a period of weeks and months.

For the longest time, I could not say the work “suicide”, believing it represented an ugly remembrance of my brother’s passing. Again, thru the help of my counselor and the healing process, I slowly felt better, to the extent that I began to think about how I might turn this terrible tragedy into something more positive. I knew that I would not only have to say the word “suicide”, but I would have to publically confront it.

Two years after John’s death, I approached one of my Senate colleagues, the chairperson of the Senate Ways and Means Committee. It was in the spring of 2001 when the legislature crafts the upcoming state budget, funding necessary state programs for the upcoming fiscal year.

Choking back sobs, I explained to the Senator that I would like to establish a line item in the budget for one million dollars to help publicize the problem of suicide in MA, and to develop strategies to confront the problem. To my utter surprise, the Senator immediately agreed to create the line item in the desired amount, with the Departments of Public Health and Mental Health collaborating in this effort. This was a first for MA, to create a program specifically dedicated to fighting suicide across the age spectrum.

The next step was to encourage my colleagues in the House and the Executive Branch to support the program. To my great fortune, I had been a member of the legislature at that point for nearly l2 years, and had developed friendships and working relationships with my legislative colleagues, Democrats and Republicans, as well as the Governor. And of course, all of these persons knew of my brother’s suicide.

The budget passed with my suicide program intact, and I realized that I had found “my cause” in the legislature. I began to speak out on behalf of the mentally ill, to fight for funding for expanded services for persons from all walks of life who struggled with the stigma of mental illness. I came to learn that the stigma of mental illness, the shame of the disease, did more to prevent effective treatment than nearly anything else.

I spoke publically for the first time in 2003 concerning my motivation for taking on the issues of suicide prevention and mental health advocacy. I disclosed that not only had I lost a brother to suicide, but I had suffered from depression for many years, went to weekly therapy, and took antidepressant medications. I felt that if my constituents understood why this was important to me, that perhaps it would become important to them too.

This unusual disclosure that brought about more support for “my cause” than I could have imagined. Constituents, colleagues in the legislature, and even people in the street thanked me for being so open, and confided that they too either suffered with a similar struggle, or had a friend or loved one who did. My disclosure made all the difference, and gave me more standing in the legislature, and publically, in my effort to erase the stigma of depression, suicide, and mental illness.

Question: It you had to say one thing to a person who has lost a sibling , what would it be?

Robert Antonioni: My message is a simple: you are not alone. There are many who love you, who have experienced your pain, your suffering, and your guilt. And that you don’t have to shoulder this burden alone. I connect them with organizations like National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. And I strongly encourage them to see a counselor who has experience in dealing with this type of loss.

* Click here to subscribe to Beyond Blue and click here to follow Therese on Twitter and click here to join Group Beyond Blue, a depression support group. Now stop clicking.