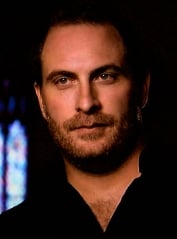

Dr. Robert Cargill and I go back several years (I tell a bit of the story here in his Noah’s Ark debunking interview). I always appreciate his perspective, because he’s got pretty serious credentials as a scientist, a biblical scholar, and a man of faith. He has a seminary degree, a Ph.D. in Second Temple period archaeology, and is an expert on Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered (check out his work on the virtual reality Qumran Visualization Project). Bob used to teach Hebrew Bible and New Testament courses at Pepperdine and shows up every now and then on the History Channel.

Dr. Robert Cargill and I go back several years (I tell a bit of the story here in his Noah’s Ark debunking interview). I always appreciate his perspective, because he’s got pretty serious credentials as a scientist, a biblical scholar, and a man of faith. He has a seminary degree, a Ph.D. in Second Temple period archaeology, and is an expert on Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered (check out his work on the virtual reality Qumran Visualization Project). Bob used to teach Hebrew Bible and New Testament courses at Pepperdine and shows up every now and then on the History Channel.

And today he contributes the longest Voices of Doubt post yet. Give it a chance, though, because I think you will be challenged and encouraged by it. He tells a bit of his story, from a conservative evangelical upbringing into academia, and how he’s learned to find a sort of balance between faith of his youth and the science of his adulthood. He’s ended up in a place that really resonates with me spiritually.

It gives me hope. I hope it does the same for you.

————-

On the Virtue of Doubt: A Brief Autobiography of the Skeptic in the Sanctuary

by Robert Cargill, Ph.D.

“Skepticism is the beginning of faith.” — Oscar Wilde

Faith is a virtue; so too is doubt. Unfortunately, doubt has far too often been pitted against faith as a problem in need of faith’s solution. Within religious circles, doubt earns a double portion of scorn for being that which must be conquered, the faithless deficiency in need of divine remedy.

The New Testament perpetuates a bipolar understanding of doubt, setting it as faith’s undesirable opposite. For instance, in Matt. 14:31 Jesus says to Peter, “O you of little faith, why did you doubt (Grk: ???????)?” John 20:27 records Jesus’ response to “Doubting” Thomas’ demand for evidence of the crucifixion saying, “Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt (Grk: ???????), but believe.” In both cases, doubt is depicted as a virtueless trait to be overcome. In fact, Jesus goes on to praise further those who did not require proof. John 20:29 states, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.”

Thus, the Bible seems to favor a simple faith that believes without proof and does not question teaching, but instead relies on the authority of the speaker, understood to be God, as validation. I soon began to ask if there were another way to understand doubt in a world, which unlike the time of Jesus now benefits from the practice of scientific inquiry. Like other biblical teachings endorsing slavery and subjugating women, I also questioned this simplistic view of doubt and wondered why so many biblical passages dismissed doubt out of hand.

I discovered that doubt and faith go together. Kahlil Gibran puts it this way: “Doubt is a pain too lonely to know that faith is his twin brother.” Or, if I may coin a scientific metaphor, doubt is the naturally selective force that drives the evolution and development of faith. Just like perseverance, which results from a self-induced desire to overcome repeated failures, and like discipline, which is a product of deliberate self-deprivation of particular desires, so too is doubt the vehicle that drives the maturation of faith. And like perseverance, discipline, and other forms of exercise, doubt is not the most pleasant of experiences, but whose alternative can be harmful to one’s health. As Voltaire stated, “Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.”

While the interplay between faith and doubt is daunting enough in the abstract, its lived manifestation fundamentally alters the foundational worldview of anyone who dares to wield the powerful sword of doubt. And that is precisely what I did.

I was raised in a Christian household (Churches of Christ) following a literalist interpretation of Scripture. The Bible said it, and that settled it, regardless of whether or not I believed it. The claims made in the Bible were unquestionable, historical fact. The Bible was infallible and inerrant, and those who dared dispute these eternally true principles were heretics in need of prayers for their souls.

My views changed during my undergraduate years as a pre-med human physiology major at CSU Fresno, where I was formally introduced to the scientific method, natural selection, and human evolution. As a Christian, I resisted this compelling new information not because of its lack of cogency or rational appeal, but because it differed from what I already believed. Still, the alternative worldview from which my parents had striven to protect me had been planted deep within my brain, and it was through this entry point — human evolution by natural selection — that doubt first gained a foothold and began to generate its thought-provoking questions in my curious mind.

I was convinced by the verifiable methods of science, but I resisted its inevitable requirement of vanquishing of my long-held belief in biblical creation. Like the child not wanting to give up on Santa, I simply did not want to admit that what I had believed all these years had been wrong. I chose instead to hold the two views — evolution and creation — in necessary tension rather than choose between the two incompatible options. It was not until I enrolled in Pepperdine University and began my Master of Divinity studies that I fully accepted human evolution through natural selection.

Ironically, it was not an understanding of Darwin’s theory that caused me to accept evolution, but rather my literary-critical studies of the Bible that convinced me of the imperfections of the text and opened the door to a full acceptance of evolution and science. This epiphany — that the Bible is not inerrant and need not be in order to convey truth — allowed me to rethink the nature of God in a way I could never have imagined nor would have been permitted in my former, juvenile way of thinking. And there I stood, an evolutionist at Pepperdine questioning all I had been taught, a skeptic in the sanctuary, thinking that I couldn’t be the only one here, but quite cognizant of the consequences of asking that question aloud.

After receiving my M.Div., I attempted to assuage my conflicted mind by taking a job building websites for non-profit and charitable organizations. But the questions lingered, and my thirst for answers led me to pursue doctoral studies at UCLA, studying biblical studies and archaeology (religion and science at their highest levels). I retained my ties to Pepperdine and the church I attend to this day. But my studies of science and the Bible — made possible by my doubt — have changed the way I understand the world, the Bible, and God. I no longer accept a six-day creation (24-hour or otherwise). I do not accept a worldwide flood. I do not accept Adam and Eve, talking snakes and donkeys, people turning into pillars of salt, the sun standing still, a firmament that holds back the waters above, a historical Exodus (early or late), or offspring that resemble what the parents were looking at during sex (Gen. 30:37-43).

These stories are etiologies that attempted to explain natural phenomena at a time before science was available to explain them. They were the best attempts of their time to bring reason and purpose to what humans witnessed everyday. However, the historicity of these early myths is not necessary to convey the truth of the biblical message, which is a love of one’s neighbor and the beneficial service of others. As the early Christian scholar Origen said, “Spiritual truth was often preserved, as one might say, in material falsehood.”

The problem, of course, with dismissing biblical creation and the flood is that Jesus mentions both of them (Mark 10:6 and Matt. 24:38-39). Christians are reluctant to let go of creation and the flood, because doing so places Jesus in the awkward position of repeating mythological stories that are not historical. An even greater problem for some with conceding that much of the Bible is not historical is that the result is not an exclusively “Christian” God. While some aspects of biblical historicity may be discounted and a distinctively Christian understanding of God retained, the honest scholar must concede that, followed to its logical end, the resulting view of God is more like a cosmic God — a prime mover that better resembles a deistic God of the early universe — than it is the personal, pocket God of modern evangelical Christianity.

And it is this contemplation of the theological chessboard seven moves from now that terrifies most Christian scholars into an immobilizing silence — within both the academy and the church — and stops them from taking the next step or even speaking aloud of its consideration. I am here to tell you, it’s OK. Some may call you a heretic, but coming out of the skeptical closet will free you to understand faith in a whole new way.

Of course, evangelicals, fundamentalists, conservatives, and biblical literalists will use my story as Exhibit A in the case of why we should not educate our children anywhere but a private, Christian institution of one’s own denominational heritage. For if they are not protected, children may be exposed to thoughts and ideas and facts and theories that are different from what their parents taught them. But, this only further demonstrates why we should encourage our children to go and explore and discover new thoughts and ideas – for it is only when opportunities, education, and experiences are limited that fundamentalists and biblical literalists retain their influence.

Christians must have the faith to doubt and ask the hard questions. If God is who the Bible claims he is, he can stand a few pointed questions. True faith is the confidence that God can survive human reasoning; for what God worth worshipping cannot withstand a few logical arguments?

Doubt and curious inquiry are the driving forces behind the acquisition of true knowledge. Thus, doubt is not treason against faith, but against doctrine and dogma — claims of truth based solely upon authority and tradition, not on methodical, persistent, and rational inquiry. In fact, I shall go so far as to assert that real faith today is often confused with doubt itself. My colleague, Dr. James McGrath of Butler University, said it best in a recent composition:

What fundamentalists call “faith” looks surprisingly like “doubt,” and what they consider “doubt” at the very least demonstrates a greater amount of “faith” than their own so-called “faith.”

Fundamentalists increasingly take measures to try to insulate themselves, and in particular their children, from other viewpoints, and in particular discussions of topics related to science or the academic study of the Bible. Where, in such actions, is any expression of faith that God will watch over them, or even faith that honest seeking after answers and consideration of the evidence will lead to the truth, and that that is a good thing? Where is faith that there is power in their message and the gates of hell cannot withstand it?

Instead, the behavior of many extreme fundamentalists reveals what they really have, deep down: doubt, fear, and uncertainty. If there is one thing that they seem in general to be certain of, it is that exposure to intelligent, rational discussion is something dangerous.

Those who refrain from asking the penetrating questions and who teach their children to do likewise are not exhibiting faith; rather, they are betraying their glaring doubt that God and their tenuous system of beliefs can survive simple inquiry.

No doubt, the brief autobiography above will cause fundamentalists to condemn my heretical betrayal of the faith and arrogant reliance on the “thoughts of men;” the steadfast to show concern for my vacillation; atheists to praise my courage; Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, and fellow Pepperdine alum Michael Shermer to chastise me for not taking the final step of abandoning religion altogether; and my mother to pray for my soul.

But this is where I stand: atop the continental divide between faith and science, with one foot in the range of rigorous academic inquiry and skeptical scrutiny, and the other on the often slippery slope of competing religious worldviews. And from this marvelous vantage point I can survey both directions and ask difficult questions of both faith and reason. I imagine that I’ll spend the remainder of my career here, the ever-searching soul attempting to mediate between the two.

I still pray, but not as much for faith as I do for the wisdom to make sense of the knowledge I accumulate, and for the courage of my convictions to live out the life of advocacy for social and individual justice that we are called to pursue. And it is on this point — the pursuit of a life of service to others — that Theists and Secular Humanists, Christians and agnostics agree. For the sheep were not separated from the goats in Matt. 25 because of their correct beliefs, nor as a result of their orthodox theology, but because of their service to others. They fed the hungry. They clothed the naked. They visited the sick. 1 Cor. 13:13 does not say, “And now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is doctrine,” but “love.” It is love that separates the true believer from the unbeliever, the faithful from the faithless. Love is faith made manifest, fertilized by doubt.

In the end, what you believe is simply not as important as what you do for others. If Christians are saved by faith, it is obedient faith in a Messiah who commanded us to serve others. And if they exist, heaven and hell will take care of themselves if you do what you’ve been asked to do. Stop worrying about life after death and live the one before it. Live a life of service. And in the mean time, ask the hard questions. Doubt everything. Challenge those in authority, respectfully, but directly. Demand explanations and require others to cite sources for all claims made. Embrace science and understand myths for what they are: early attempts to explain a world before science while communicating cultural ideals. And remember: true knowledge is the result of doubt, not blind faith, for “only the one who knows nothing doubts nothing.”

As the Chinese proverb says, “With great doubts come great understanding; with little doubts come little understanding.”

————-

Thank you, Bob. You can keep up with Dr. Cargill at his blog, on Twitter, on Facebook, on YouTube, and a lot of other places via his official website at bobcargill.com.

Previous posts in the “Voices of Doubt” series…

• Dana Ellis: Haunted by Questions

• Rachel Held Evans on Works-Based Salvation

• Winn Collier: Doubt Better

• Tyler Clark on Losing Fear, Losing Faith

• Rob Stennett on the Genesis of Doubt

• Adam Ellis on Hoping That It’s True

• Nicole Wick on Breaking Up with God

• Anna Broadway on Doubt and Marriage