This Spring, Jews worldwide will begin observing one of Judaism’s most joyous and celebratory annual holidays (or “holy days”): Purim, or the Feast of Lots.

Purim always falls upon the fourteenth day of the Hebrew month of Adar (except in the city of Jerusalem, where it uniquely falls upon the fifteenth day of that month). However, that fixed date of 14 Adar on the Jewish religious calendar does not always coincide with February 23/24 on the secular Western (Gregorian) calendar.

The traditional Jewish calendar is a lunar calendar, which means that it counts and calculates its lunar months somewhat differently from how the widely-used Gregorian calendar (which is a solar calendar) reckons its own months. This means that there is a certain amount of built-in “drift,” from year to year, between the two calendars.

In 2012, for instance, Purim (14 Adar on the Hebrew calendar) began at sunset on March 7 and ended at nightfall on March 8, 2012. In 2014, by contrast, Purim begin at sunset on March 15 and ended at nightfall on March 16, 2014.

Purim typically starts one date later in Jersalem, but why? Well, that requires getting into the nature and background of this particular Jewish holiday. Purim celebrates events set in ancient Persia, as described in the biblical book of Esther. At the time, many Jews were living within the mighty Persian Empire, and one day the king of Persia decided he needed a new queen. Esther, a beautiful young Jewish woman, caught the king’s eye, and thus became the new Queen of Persia.

However, Esther didn’t reveal to her royal husband that she was actually not Persian herself, but in fact belonged to Persia’s Jewish minority.

Before long, a scheming court advisor began plotting to exterminate all of the Jews then living within the bounds of the entire Persian Empire, and even successfully obtained the king’s permission to do so. In order to determine the date selected for the planned genocidal massacre (which turned out to be 13 Adar on the Hebrew calendar), this wily advisor drew lots (purim in Hebrew); hence the subsequent holiday’s name of Purim, or the Feast of “Lots.”

Following a series of additional intrigues, Queen Esther at last revealed to her royal husband the fact that she was Jewish herself, and that the planned extermination of every Jew in Persia would therefore include her in the body count.

The king had his sinister court advisor executed. Unfortunately, however, he could not belay his own previous order; the royal decree to execute all Jews in Persia still stood.

In order to spare Esther and her people, the king of Persia permitted his queen (and her cousin, who had previously proved his own loyalty to the king) to issue a new decree of their own: the Jews of Persia were granted the legal right to launch a pre-emptive strike against any and all possible Persian would-be attackers.

On 13 Adar, the calendar day that had been chosen by lots for the anti-Jewish genocide, the Jews of Persia struck first, pre-emptively killing many thousands of their would-be Persian executioners and thereby saving themselves from certain and utter destruction.

Within unwalled cities throughout the Persian Empire, the Jews battled their enemy on 13 Adar, before resting and celebrating their victory on 14 Adar. This is why Purim is celebrated on 14 Adar, in most places in the world today.

However, within the capital city of the Persian Empire, the fighting extended throughout both 13 and 14 Adar, with rest and victory celebrations coming only on 15 Adar. It was therefore deemed fitting that Purim be celebrated on 15 Adar by the Jewish populace of walled cities – which, today, basically just means Jerusalem.

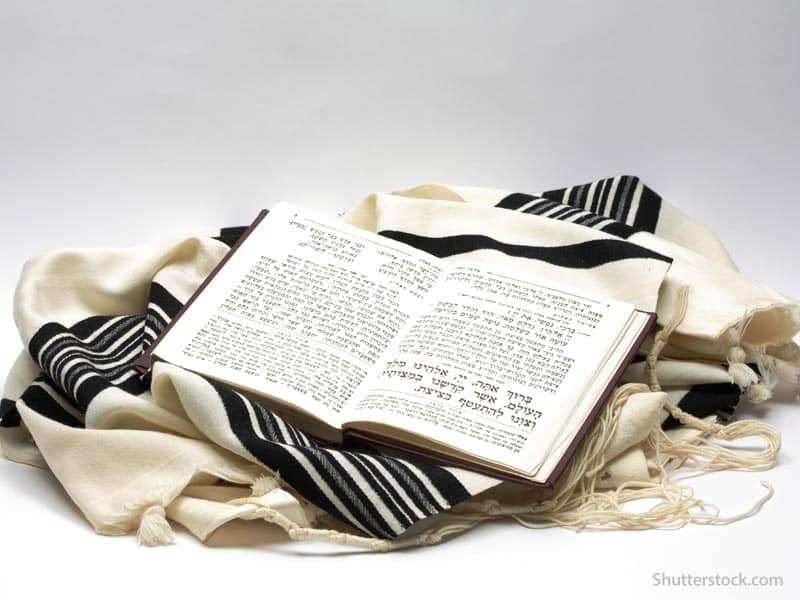

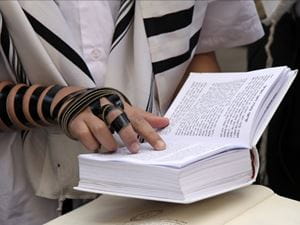

Regardless of its date, Purim is a joyous commemoration of the Jews’ deliverance from annihilation in ancient Persia. Today, Purim is celebrated with synagogue readings of the book of Esther, wearing costumes which conceal one’s true identity (much as Esther initially hid her own Jewish identity from the King of Persia), giving gifts of food, making charitable donations, and enjoying festive meals. I’d like to take this opportunity to wish my Jewish readers around the globe Chag Purim Sameach (Hebrew for “Happy Purim Holiday”) and Freilichin Purim (Yiddish for “Festive Purim”)!