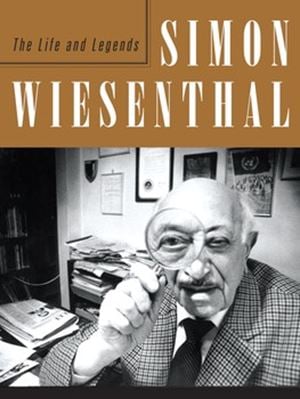

The Life and Legends: Simon Wiesenthal

Introduction

The Glass Box:

The horror enveloping the city’s Great Synagogue was almost unbearable, and hysterical shrieks rose from people crowding around the building. The newspapers reported that there were tens of thousands present and described heartbreaking scenes. There were cries of “Mama! Papa!” and many fainted. Small children were also to be seen.In the main hall of the synagogue stood a glass box, five feet long. In it were thirty porcelain urns, painted with blue and white stripes. According to the newspapers, they contained the ashes of 200,000 Jews who had been murdered in the Holocaust. The mayor was there, as well as other dignitaries and rabbis. Speeches were made and prayers intoned, and then the glass box was loaded onto a police vehicle, to be carried through some of the city’s streets; the vehicle had trouble making its way through the crowds.

The man who organized this historic spectacle was Simon Wiesenthal, then forty-one years old. From the day he was released from the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria he had lived in the nearby city of Linz and occupied himself with searching out Nazi war criminals. The ashes of the dead had been collected at his initiative at concentration camps and other detention sites across Austria.

“The glass box,” he wrote later, “had suddenly become a kind of looking-glass, in which the faces of many, many were reflected—friends from the ghetto, companions from the concentration camps, people who had been beaten to death, died of starvation, been hounded into the electrified fence. I could see the panicked faces of Jews who were whipped and clubbed into the gas chambers, chased from behind by human animals devoid of conscience or feelings, who would not hear their lone plea: to let them live.”

By then Wiesenthal already knew several Israelis, but not many Israelis knew him. The mayor of Tel Aviv, Yisrael Rokach, for one, didn’t know who he was when Wiesenthal first contacted him, in Yiddish, a few months before. But Rokach seems to have been impressed by Wiesenthal’s assertive style. It was more like an order than a query, request, or suggestion: the Association of Former Concentration Camp Inmates in Austria had decided to transfer the ashes of the martyrs to Israel and to honor the city of Tel Aviv by making it the recipient, Wiesenthal wrote. There was no way to refuse, and Rokach replied that Tel Aviv would accept the urns with a “tremor of sanctity,” although he had no idea what to do with them. The annihilation of the Jews haunted many of the inhabitants of Israel.

They were tormented by the pain. Already in 1946, ashes brought from a camp in Poland had been interred in Israel. But even in 1949, nobody really knew the right way to go about mourning six million dead or how to perpetuate their memory. The law on prosecuting Nazis and their collaborators would only be enacted a year later; the official Holocaust Memorial Day would be designated two years later, and the law establishing the State Memorial Authority, Yad Vashem, would be passed only in 1953. When Wiesenthal came to Israel, the Holocaust was still wrapped in silence. Parents never told their children what they had experienced; the children never dared to ask. Holocaust survivors made people flinch with anxiety, embarrassment, and feelings of guilt. They were not easy to live with: How can you share an apartment building with them, work with them, go to the movies or the beach with them? How can you fall in love with them and marry them? How can their children go to school with yours? It’s doubtful that any other society ever faced so difficult or painful an encounter with “the Other,” to use a phrase that came into currency later.Many of the Israelis who had settled in the country before World War II, or were born there, tended to relate condescendingly to Holocaust victims and survivors, identifying them with the Jews of the Diaspora, whom they despised as the polar opposite of the “new Hebrews” they were trying to create in the Land of Israel, in the spirit of the Zionist vision. It was customary to blame the victims for not coming to the country beforehand, remaining in Europe instead and waiting to be slaughtered without doing anything to prevent it.

In 1946, Wiesenthal attended the first Zionist Congress since the Holocaust, held in Basel, Switzerland, and the thought ran through his mind that the leaders of the Zionist movement deserved to be put on trial, like the heads of the Nazi regime who were tried in Nuremberg. “I took a good look at those who were our ‘leadership’ and had done very little to save Jews,” he related. He was referring to Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, among others. By bringing the ashes of the victims to Jerusalem for burial, Wiesenthal was demanding of the Israelis that they at long last confront the Holocaust, in the same way that in days to come he was to demand it of the other nations of the world. The institutions and the officials involved in organizing the funeral tended to look upon the matter as a nuisance, but Wiesenthal would not let them alone. At first he had written to Yad Vashem, but at that time it was only a private society operating out of a three-room office and having a hard time paying the rent. “We regret that our project is as yet unable to receive this sacred consignment,” the organization wrote to Wiesenthal, and so he turned to the Tel Aviv municipality. The heads of Yad Vashem had no choice but to acquiesce, but they soon changed their minds and demanded that the glass box be buried in Jerusalem. Wiesenthal went along with that as well: “We believe that for diplomatic and national reasons at this time we must do everything to concentrate in Jerusalem all things and all projects that symbolize the link between the Diaspora of our people and the State of Israel,” he wrote, using the first-person plural, as was his custom.But now the need arose to decide who would finance the project. Wiesenthal assured Mayor Rokach that the organization he was acting for would cover all the shipping costs, but he requested funding for airplane tickets and a ten-day stay for himself and one companion. Yad Vashem replied immediately that it had no money. The request led to a lengthy correspondence, and eighteen months went by. It was a dramatic and bloody period.

Between his first letter to Yad Vashem in January 1948 and the funeral, a war had been waged and the State of Israel had been declared. Wiesenthal, who was a keen stamp collector, had an idea: the Israeli Postal Service should issue stamps in memory of the Holocaust, and the revenue would be used to cover the expenses of the memorial project.But it was not only the issue of funding that held up his initiative. The fledgling state needed an aura of heroic glory, and some of the officials handling the matter thought the remains of Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement, should be brought from Vienna for reinterment in Jerusalem before the ashes of the Holocaust victims from Austria; Herzl was a symbol of triumph, the Holocaust represented defeat. So this is what was done. An argument also arose as to the respective roles of the state and the Chief Rabbinate in burying the ashes of those who perished in the Holocaust, an echo of the ever present confrontation between the secular and the religious. And out of this arose the question of whether the urns that Wiesenthal wanted to bury in a Jewish cemetery in Israel really contained only the ashes of Jews, or whether there were also ashes of gentiles mixed in with them.In the end, Wiesenthal lost his patience.

He cabled Yad Vashem that he was on his way to Rome, where he would board an Italian airliner with the ashes and fly to Israel. Please make all the preparations, he demanded. Only now did Yad Vashem convene a committee, which hastily organized the ceremony as mutual recriminations flew through the air between the various parties involved. These found their way into the newspapers. There was a scandal, but at the last minute the speaker of the Knesset managed to read into the parliamentary record a state declaration of mourning, and the papers gave the event extensive coverage.This was Wiesenthal’s first visit to Israel. He entered the country on a Polish passport. He was welcomed respectfully and no one troubled him with the obvious questions: Where exactly were the ashes collected? How can we know if they are really the ashes of the victims? And how did you determine that the number of Jews who were killed in Austrian concentration camps was 200,000? One newspaper apparently thought this wasn’t enough, and wrote 250,000. The papers tended to conceal the fact that these were in fact symbolic samples of ash and described the urns as containing all the ashes of the hundreds of thousands of victims.Wiesenthal was very emotional.

“As I followed the box of ashes,” he wrote, “I remembered my family members, my friends and companions, and all those who paid with their lives for one single sin—being born Jewish. I looked at the box, and I saw my mother’s face the way it looked the last time I saw her on that fateful day when I left home in the morning for forced labor outside the ghetto and I did not know that I would not see her when I returned in the evening, nor ever again.”

The burial of the ashes was meant to be only the first stage in a much more ambitious program: Wiesenthal hoped to have a huge structure erected in memory of the Jews who perished in the Holocaust, what he called a mausoleum. Before the Nazi occupation of Poland, he had studied architecture, and he designed a memorial site that he proposed should be built in a forest outside Jerusalem, to which the ashes should eventually be moved from Sanhedria. He sketched a kind of platform paved with marble, topped with two menacing towers, an exact replica of the gate of the Mauthausen camp, and a stone dome over a round memorial hall with a black floor. This was the first time he tackled what was to become a vast enterprise. He radiated resourcefulness, self-confidence, and conviction. He was already revealing his innate skill at public relations. Before leaving for Israel he had sent the design for the mausoleum to a large number of Jewish organizations and individuals in various countries. The project was also meant to mark the closing of the Jewish displaced persons’ camps in Austria, and the migration of their inmates to Israel. He received many pledges of help. When he sent a copy of the plan to Ben-Gurion in April 1952, he asserted: “We can raise the sum of money needed for this within two years.” The prime minister’s office informed him politely that it had conveyed his proposal to Yad Vashem. Wiesenthal did not demand to be appointed the architect of the project, but probably assumed that he would be. If his proposal had been accepted, he might have settled in Israel and practiced architecture, instead of remaining in Austria.

Ohel Yizkor—the Tabernacle of Remembrance, which would eventually be built at the Yad Vashem complex in Jerusalem—resembles the memorial hall that Wiesenthal had sketched. Some of the ash that he had brought was later transferred from Sanhedria to Ohel Yizkor, but he was not given a role in its design, and he never returned to architecture.The drama of Simon Wiesenthal’s life is stored in hundreds of files containing some 300,000 pieces of paper: letters he received and, mainly, copies of letters he wrote in his sixty years of work as a “Nazi hunter.” The first file begins in 1945, when he was a walking skeleton, weighing ninety-seven pounds, who had just left Mauthausen with no hope and no future. About sixty feet down on the same shelf, there’s a file from the 1980s, containing the following handwritten note: “Darling Simon, Take good care of yourself and stay happy. I love you and we all need you, Elizabeth Taylor.”

A tireless warrior against evil and a central figure in the struggle for human rights, Wiesenthal enjoyed worldwide admiration. Hollywood adopted him as a cultural hero, as did the scores of universities that awarded him honorary degrees. American presidents hosted him in the White House. Wiesenthal relished every moment of acclaim, but when he said that President Jimmy Carter needed him more than he needed Carter, he was right. One of the officials of the Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles observed that if he had not existed, Wiesenthal would have had to be invented, because people all over the world, both Jews and gentiles, needed him as an emblem and a source of hope.

This was his life’s goal. Sometimes he would go out on small detective missions, extracting leads from talkative neighbors or barmen, mailmen, waiters, and barbers. An acquaintance compared him to Inspector Clouseau, the bumbling detective in The Pink Panther. His faith in the liberal system of justice and in America, combined with his communication skills, made him very much a man of the twentieth century. The concept of Holocaust commemoration that he developed was a broad, humanistic one. In contrast to the memorializing of only the Nazis’ Jewish victims fostered in Israel and by the Jewish establishment in the United States, Wiesenthal tended to view the murder of the Jews as a crime against the whole of humanity, and he tied it in with the atrocities committed by the Nazis against other groups, such as incurable invalids, Gypsies, homosexuals, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. In his eyes, the Holocaust was not only a Jewish tragedy, but a human one.

and one of them compared him to a hitchhiker who took over the driver’s seat. Others likened him to the legendary liar Baron Munchhausen. Actually, Wiesenthal worked for years in the service of Israel’s secret intelligence agency, the Mossad.

He was involved in efforts to locate and prosecute hundreds of Nazi criminals, and assisted in the conviction of dozens. His endeavors were remarkable, especially in view of the fact that after the defeat of the Third Reich, most of those involved in Nazi atrocities had gone unpunished. They had integrated themselves into the lives of their communities in Germany and Austria and other countries and were not called upon to answer for their crimes. Some of them had done well in politics, in the civil service, in the judiciary, and in the educational and economic systems.

This happened not only because the Germans and the Austrians took an indulgent attitude toward the criminals, but also because of the Cold War. More than once Wiesenthal saw that offenders he had located and wanted to prosecute were employed as secret agents in the service of the United States or other countries and, in at least one case, of Israel. “The Nazis lost the war, but we lost the postwar period,” Wiesenthal used to say.Wiesenthal died in September 2005, at the age of ninety-six. His daughter, Paulinka Kreisberg, was flooded with consolation messages. Beatrix, queen of the Netherlands, and Abdullah, king of Jordan, were among those who wrote, as were Laura and George Bush, as well as presidents and prime ministers, legislators and mayors from all over the world. The U.S. Senate unanimously passed a resolution commemorating his life and accomplishments. Someone sent condolences on behalf of Muhammad Ali, the legendary boxer.

That may have happened because of the constant and repeated pressure that Wiesenthal had exerted on the city of Berlin until it gave in to him and named a street after Jesse Owens, the black sprinter who defeated Hitler’s athletes in the “Nazi Olympics” in Berlin in 1936. From Jerusalem, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon wrote: “The State of Israel, the Jewish people and all of humankind owe a great debt to Simon Wiesenthal who devoted his life to ensuring that the Nazi atrocities will not be repeated and that the murderers will not go unpunished.”But his daughter’s heart was touched most by the private letters she received from innumerable individuals, among them hundreds of members of the “second generation”—the children of survivors, for whom the heritage of the Holocaust was a key part of their identity. Many of those children felt a deep identification with Wiesenthal. Esti Cohen, a native of Israel, wrote to Paulinka Kreisberg, “At the age of six, I used to have shoes ready next to my bed so that if the Nazis came in the night, at least I would have shoes, and not be like my mother in the ‘death march’ from the concentration camps at the end of World War II.” She attached to her letter a photocopy of her Israeli ID card, with a yellow star stuck onto it.Wiesenthal related that once when he was a prisoner at the Janowska concentration camp in Lvov, in Ukraine, he was in a group of inmates ordered to dig a deep ditch. “We knew that soon the ditch would be full of bodies,” he said. “The victims were already being marched up. Women and girls.

Then I caught the desperate eye of one of the girls. ‘Don’t forget us,’ is what that look said to me.” On another occasion, he said, he imagined meeting with the victims in heaven, and he was determined to say only four words, “I didn’t forget you,” the phrase that became his personal motto. More than anything else, Wiesenthal deserves to be remembered for his contribution to the culture of memory and the belief that remembering the dead is sanctifying life. Ironically, the more years went by and the more unlikely it became that the surviving Nazi criminals would be brought to justice, the more the Holocaust became a universal synonym for evil, a warning sign for every nation and every person. This happened, to a large extent, thanks to the efforts of Simon Wiesenthal. Nobody did more than he did in this respect. But even at the height of his fame as a “Nazi hunter” and as a humanist authority, he remained a lonely man, haunted throughout his adult life by memories of the horror. He was a tragic hero, always cloaked in the mysteries of his life; it is no easy task to decipher his secrets. As he walked behind the glass box in Jerusalem, Wiesenthal thought not only about the murdered millions, but also about the murderers: “I was reminded of Eichmann,” he wrote later. “That it was possible that the following day he would read in the newspaper about the ceremony and that a smile of satisfaction would come to his lips. . . . In my mind’s eye, I foresaw the day when my silent prayer would be heard, the day on which the murderer of my people would be taken to the land of the Hebrews. I swore that I would not remain silent and I would not rest until that longed-for day came.” This was a statement that was both true and untrue, like much of what Wiesenthal wrote.

Excerpted from Simon Wiesenthal by Tom Segev. Copyright © 2010 by Tom Segev, Translation copyright © Ronnie Hope. Excerpted by permission of Schocken, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.