Pixabay.com

Moksha is one of the four purusharthas or “goals” of a Hindu life. These goals are tied to a Hindu’s age and their current place in life. The four goals are kama, artha, dharma and moksha. Moksha is the ultimate goal of any Hindu’s life, but it is not meant to be pursued until all the other goals have been achieved. This is because attaining moksha requires a great deal of time, effort and focus.

The first goal for Hindu’s is kama. The kama of this goal is the same kama found in the famous book the “Kama Sutra.” Kama, unsurprisingly, means desire. Kama does not, however, always refer to sexual desire. Sexual pleasure is a part of kama, but there is a great deal more to it. Kama, as a whole, is made up of all sorts of sensual and aesthetic pleasures. Kama could mean a fierce enjoyment of such aesthetic pleasures as the arts, music, dance and poetry. Sensual pleasures could include soft cloth, delicious food, and yes, good sex. Hindus emphasize, however, that pursuit and enjoyment of these pleasures should always be done in a virtuous manner. Kama should never be one sided, and a virtuous Hindu must both give and receive kama though actions such as creating works of art, performing dances for others or singing.

Artha means “abundance” or “success.” It is largely this goal that keep a person from working to attain moksha when they are in the prime of their life. Chasing after moksha generally means leaving behind a person’s loved ones which does not mesh well with the goal of artha.

Artha is tied to the stage of a Hindu’s life. These stages of life, or ashrama, are student, householder, forest dweller and renunciate. A student is just that, someone who is engaged in studying. In this case, a young person would be studying and learning the religious texts such as the Vedas. This may include learning to recite passages from the texts in perfect ancient Sanskrit or learning how to lead puja and worship at a home shrine. This stage lasts until a person marries, and they become a householder.

It is during the Hindu’s time as a householder that artha is most important. During this stage, a person is supposed to work to grow the material and monetary abundance of their family as well as the family’s power. So long as this is done in an ethical manner, Hindus do not look down on such attempts to reach monetary success like Christians often do.

The emphasis on virtue has to do with the third purushartha, dharma. The word dharma has no good translation into English, but it is central to Hinduism. Dharma is the power that upholds the world and keeps the universe balanced on a cosmic level. Everything is considered to have dharma even inanimate objects. The dharma of a rock is to be rock. For human beings, dharma is based on a person’s stage of life, caste and the individual themselves. Dharma means making choices to live a ritually correct life according to who a person is in this life. Their dharma will be different in the next life. Hindus hope that they will be reborn into a better station and so have the dharma of someone with more power, money or influence.

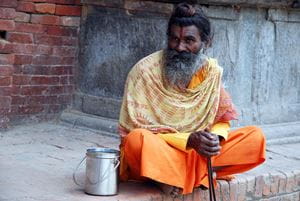

The final stage of life ties to the final goal of Hinduism. The last ashrama is that of a renunciate who is seeking moksha. Renunciates are those who leave behind their family and abandon all personal and sensual pleasures following the birth of their first grandchild. They literally renounce society and familial ties. Not all Hindus choose to pursue the path of the renunciate. Some are perfectly happy to focus on earning a better rebirth instead of working to attain moksha.

For those that choose to work toward moksha, there is no single path. Each tradition in Hinduism has a different idea of how to achieve that final liberation, and there are many different paths to moksha to be found in each tradition.

Many traditions emphasize the importance of the guru, a knowledgeable teacher who will help the Hindu seeking moksha make sense of the world and let go of their ego. This is central to almost all paths to moksha: letting go of desires and the ego. In some traditions, this means that when moksha is attained and a person dies, the person’s entire self will be subsumed into the Divine. In other traditions, the person will keep a sense of self, but they will become part of a greater whole.

One tradition for seeking moksha is that of yoga. Far from the Western exercise classes, Hindu yoga is about the mind not the body. The poses that most Westerners are at least passingly familiar with are only a small part of the practice. Most of the time is spent meditating on ignorance and working to remove “the veil of ignorance” from a person’s mind. Some traditions have people do this by focusing on a particular god, like Krishna. Other traditions do not hold to a personal creator deity but rather an impersonal creative force, and so meditating on one god is actually counterproductive.

There are as many paths to moksha as there are Hindu traditions. Were there a single way that was easily defined and consistently successful, there would be far fewer Hindu traditions. Instead, Hindus must do as all religious people do: follow what they believe and have faith that they are following the correct path.