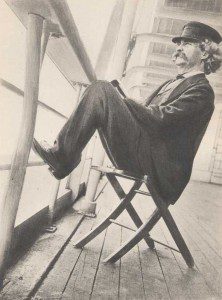

In Mark Twain’s full and unexpurgated Autobiography he expresses his opinion, with exquisite clarity, on what he would like done to one James Paige:

In Mark Twain’s full and unexpurgated Autobiography he expresses his opinion, with exquisite clarity, on what he would like done to one James Paige:

If I had his nuts in a steel trap I would shut out all human succor and watch that trap till he died.

And who was the James Paige who brought out this savage desire for revenge in Mark Twain? Paige was an inventor with an idea for a typesetting machine. He convinced Sam Clemens (Mark Twain’s real name) that his invention would revolutionize the newspaper and publishing business and earn the bestselling author a fortune far beyond his literary earnings.

Clemens always hoped to make a bundle doing something other than writing or speaking. He thought he saw his chance with Paige’s plan for a typesetting machine. Remembering his sweaty days as a “printer’s devil”, toiling with heavy trays of type in hick print shops, he also dreamed of being present at the creation of a new technology that would make printing speedy and accurate.

Paige talked a good story. As Clemens ruefully recalled, Paige “could persuade a fish to come and take a walk with him.” The author was soon convinced that Paige’s machine was going to be the biggest thing since Gutenberg, and he drained his bank accounts to become the biggest investor in the project. However, the enterprise was bedeviled by delay after delay, Costs rose, contracts were revised, and soon Clemens had sunk $150,000 into a project he had been assured would not cost more than $30,000. By the time Paige had completed a working prototype, his machine was obsolete, overtaken by new and superior typesetters. Clemens, the main investor, was left on the edge of bankruptcy.

Mark Twain could have avoided all of this pain and loss had he noticed what’s in a spelling mistake, or a typo. He could simply never get the name of the inventor right. Whenever he wrote to Paige, or about him, he misspelled the name, leaving out the I. I’ve gone through his correspondence and his journal entries on this theme. Again and again, he wrote “Page” instead of “Paige.”

Mark Twain had decided to invest all his money in a machine that promised to make printing more accurate. Yet he could never spell the name of the machine or its inventor correctly. We might notice the dreamlike symbolism of leaving out the I. The whole wretched enterprise left out the author’s I, his self-interest.

If Freud had known about this, I am certain he would have added Mark Twain’s recurrent spelling mistake to the cases of “Freudian slips” that compose the most interesting pages in his Psychopathology of Everyday Life. Freud considered, correctly, that it is always significant when we screw up or forget a name we have every reason to know well.

There’s a message in this, for you and me. If he’d ever managed to laugh about this (his humor sometimes failed him, as the uncensored memoirs reveal) Mark Twain might have distilled it in a snapper like this: Notice what’s in a typo. It’s one variant of a general rule for navigating by synchronicity, or isomorphy, that I will state as follows:

Notice what’s showing through your slip.

For a full account of the role of coincidence and dreams in Mark Twain’s life, please see my Secret History of Dreaming.