I did not walk out of that cathedral converted, exactly, but I did leave it a changed man. I had been unhorsed by a sense of wonder, and when I picked myself up off the ground, began a search for a God I now knew was there. ing to church and being nice. Who needed that? Not me.

And then, on a group trip to Europe, I walked into the Chartres cathedral. Nothing in my experience had prepared me for that Gothic masterpiece, constructed for the greater glory of God in the 12th and Eventually, I found Him.

That was 30 years ago. One recent weekday, talking with my wife about how I have become mired in everydayness, and was struggling to reconnect with God, I told her, “I need to see Chartres again.” By that I meant that I needed to have an encounter with holy awe to refresh me spiritually.

“I guess that’s how you and I are different,” she said. “You have this need for spiritual fireworks. I find God in everyday things.”

As a theological matter, I agreed with her that God really is present in ordinary life. For whatever reason, I find it hard to see Him in it, at least in a way that moves me.

That evening, I went to Vespers at our Orthodox parish, a humble mission church in the south Louisiana countryside. It was the feast day of St. Seraphim of Sarov, a mystic Russian monk of the 19th century. As I listened to the choir sing about him, I recalled an encounter the saint had with a disciple named Nikolai Motovilov.

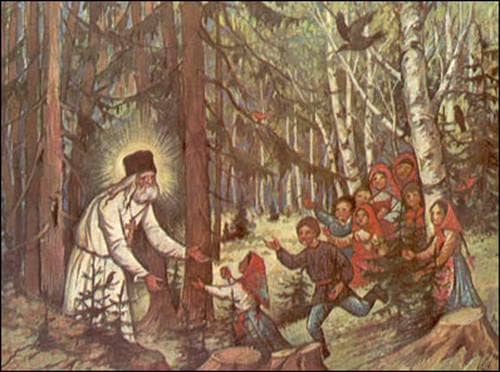

In 1831, Motovilov, a businessman, had gone to visit the old hermit in the forest near Seraphim’s monastery. In their meeting, Seraphim told the businessman that the Lord had revealed to him that he, Motovilov, had spent the early part of his life asking his elders what the point of the Christian life is. All they told him was to say his prayers, go to church, to be good, and to stop asking questions. That, Seraphim said, did not satisfy Motovilov – and understandably so!

The holy monk explained that prayers, churchgoing, and good works are ways to help us reach God, but they are not the point of the Christian life. The point is to acquire the Holy Spirit – that is, to encounter God personally, and to be changed by Him.

That’s fine, said Motovilov, but how can we know that the Holy Spirit is in us? How can we see Him?

The gentle monk explained that because we don’t expect to meet Him in the everyday, we inadvertently blind ourselves to the possibility.

Suddenly, Motovilov and the monk were surrounded by dazzling light, a light Motovilov would later describe as like “the center of the sun.” The holy elder told the awestruck Motovilov that it is like this all the time with the faithful who dwell in the Spirit, though God veils our eyes. God, said Seraphim, is not a God who is far away, but who is very close to us. We rarely see Him in this extraordinary way, but then, with those who see with the eyes of total faith, He does not have to.

That was a Chartres moment for the seeker Motovilov. Here’s the lesson: a seeker doesn’t have to go to Chartres, or to visit a holy hermit in the Russian forest, to experience the awesome presence of God. For men and women of faith, Chartres is not on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, but six miles away, in a country chapel. The Russian forest is not thousands of miles away, but in my own backyard.

I realized that leaving the spiritual slough of everydayness to the joy and peace of God’s presence was not a matter of making a pilgrimage to a different place in the world, but of making a pilgrimage to a different place within myself. Leaving church that night, I kissed the icon of St. Seraphim, and thanked him for showing me how things really are.

Rod Dreher can be reached at rod@amconmag.com