One of the paradoxes of the human condition is that even though we know that we are mortals, we wish that those we love could live forever. We also wish that our own lives could be lived out with less pain, suffering, uncertainty and fear. But incurable diseases know no boundaries of geography, religion, race or ethnicity. Life-altering sicknesses eventually make their presence felt in our lives, forcing unexpected changes.

But the ways we react to these changes vary in each culture and in each family. In the last decade, new advances in medical technology both have made it possible to live longer with serious disease and have complicated the choices we have in treatment. Collectively, these new realities have impacted the ways communities, families, and individuals are responding to illness.

If you or someone you love is facing such a life-threatening illness, then you may be asking not only the practical questions - "How will I find the support, comfort, strength and care I need to get through this?" but the existential questions--"Why is this happening? Why now? And what choices lie ahead?"

Addressing both sets of questions is at the heart of an honest, spiritual approach to illness. Being honest about serious illness begins with admitting that the ultimate causes of disease cannot be fully explained, well-intentioned prayer cannot save everyone, and medical technology has its limits. But what you do have power over is the way in which you can respond to serious illness.

Your response can lessen your pain and suffering, enhance the quality of your life, and in many cases actually extend life. A genuinely spiritual response to disease can turn a situation of deterioration and despair into an opportunity for finding purpose, evoking courage, fostering strength and promoting healing.

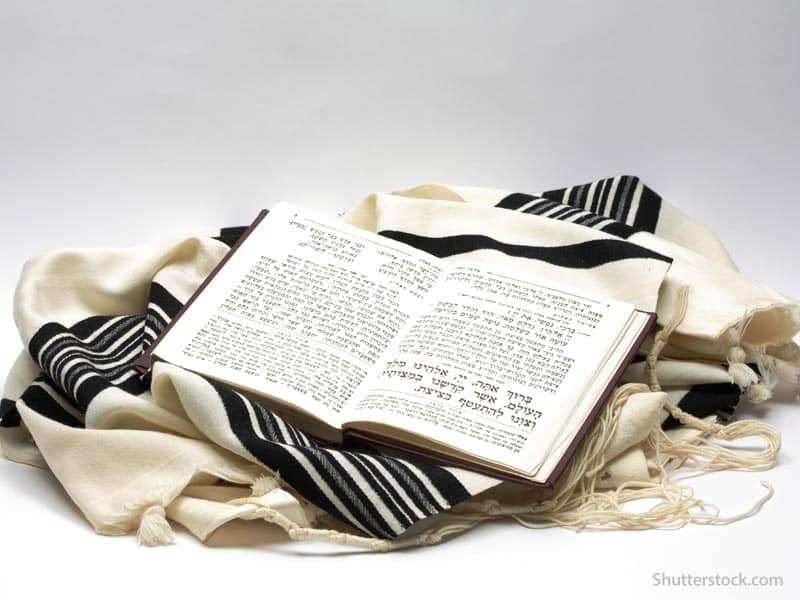

For centuries, Jews have developed a worldwide reputation for our ability to persevere through countless trials, and to survive the most brutal of regimes. In this way, Jews have been forced to make meaning out of suffering. That said, though, we have no corner on the survival market, nor a magic formula to bring to a time of crisis. In fact, Jews have drawn on strength from many sources-- from the wisdom contained in spiritual practices, from a deep sense of responsibility for one another, and from a covenantal connection to God.

Even more important, though, is the sense that our lives are bound to one another - that in the connections we have to one another we experience what it means to truly live. As philosopher Martin Buber taught, we meet the sacred in the place that exists "in between" one another. A spiritual path centered on the self is only partial. In articulating a Jewish spiritual approach, we highlight our connections to each other, reflecting on the ethical teaching of the early rabbis "all the people of Israel are reliant on one another."

There is a profound integration in a Jewish spiritual approach, one best articulated by the 19th century sage Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav when he said: A person reaches in three directions: Inward, to oneself, up to God, and out to others. The miracle of life is that in truly reaching in any one direction, one embraces all three.

Reaching in, up, or out is no easy task. It would probably be easier to deny that disease causes change. But as difficult as it is to be honest about your fears of the future, it is only by articulating those fears that a vision for the time ahead will emerge.

How Jewish Resources Can Help

The Jewish approach to serious illness does not deny the reality of the disease, paper over the suffering, or expect "presto you're healed!" miracles. It is one that acknowledges that living with disease or debilitation is a profound challenge, which requires courage, sensitivity and reflection.

In this spirit, generations have turned to the Psalms--many of which are written from a place of brokenheartedness. Three thousand years before the birth of the blues, David sang of woe, loss, love, and despair, as in the 77th Psalm, where he cried:

"I moan, I try to speak and my soul feels suffocated."

Or in the 16th Psalm where he wrote:

"As a woman whose labor pains turn to sweet joy, I must see my fate as beautiful.even though my nights feel imprisoned."

David's words are a tremendous Jewish resource because they directly convey the "reaching in," the connection to the personal, emotional landscape of suffering. Other Jewish texts speak of the "reaching out"--the relationships that develop among people in the journey of illness. A Talmudic discussion illuminates this idea:

Rabbi Huna taught that one who visits the sick lessens one-sixtieth of the pain. But other scholars challenged him, saying: "If that is true, then why not send sixty people to visit a patient?"

Huna replied: "Sixty people? You have misunderstood me. It is not the number of people that lessens the pain--it is the visit itself! On each visit a sixtieth will be lessened, and this will give relief to the pain."

In addition to the psychological and spiritual resources in Jewish sources, the Jewish healing tradition emphasizes the role that medicine plays in the healing process.

Take, for example, this clever parable on healing from the Talmud:

Two esteemed scholars, Rabbi Ishmael and Rabbi Akiba, were once walking in Jerusalem. A sick person came to them and asked for a remedy. A man nearby, who overheard the conversation, challenged the Rabbis. "God has sent sickness, and yet you are teaching this man how to be cured! Are you not working against God's will?"

The Rabbis answered his question with a question. "What kind of work do you do?" they asked.

"I am a wine grower," the man replied.

"God created wild vines and you cut off the fruit?" the Rabbis asked him.

"But that is the only way to produce more grapes!" the man answered back.

"That is how it is with a sick person," the Rabbi explained. "One must take care of the body to enjoy life. The drugs we recommend are like the fetilizer which you use to strengthen the soil if it becomes weak." (Midrash Temurah, chapter 2)

In this story, drugs are not seen as against God's will--in fact, taking the right drugs is exactly what the Creator intended. The early rabbis understood creation as somewhat incomplete, and they had a belief that nature requires human action to complete it.

While we can learn from illness and facing our mortality, we cannot fully explain why we get sick or why we die. But that does not stop us from asking the questions that illness provokes. What is life all about? What is God's role in it? What endures? What gives us hope?

Finding Meaning

Beyond developing a new awareness about your body's physical reactions to illness, the first stage in a spiritual approach to illness explores the "why?" questions. You may be asking, "Why is this happening to me?" or "Why now?" or "Why does God allow disease and death in this world?"

To respond to this question, we turn to stories:

A man goes to Reb Dov Ber with a question:

"How can I learn to accept the bad things in my life?" he asks the great sage.

Reb Dov Ber replies: "I do not have an answer, but Reb Zosha has one. Go to the town of Anapol and ask him your question."

The man traveled to Anapol and inquired among the townspeople as to the whereabouts of Reb Zoosha. They pointed him to a rundown shack on the outskirts of town. The man knowcked on the door of Reb Zoosha's home, only to be greeted by an old man, frail and sick, who wore ten layers of clothing to ward off the intense cold.

"I am looking for Reb Zoosha!" the man asked.

"I am Reb Zoosha," replied the old man.

"Reb Zoosha, may I ask you a question?" the man said.

Reb Zoosha asked the man to come in and sit down. "I would offer you something to eat if I had some food," said Reb Zoosha as he sat down.

"That you, Reb Zoosha, but it is not food I hunger for. I must learn, how can I accept the bad things in my life?"

Reb Zoosha began to laugh, exposing his toothless grin.

"How can you be laughing at such a question?" the man demanded.

Reb Zoosha replied, "Because I could never answer it! I haven't had a bad day in my whole life!"

How could Reb Zoosha say such a thing? Surely he had been ravaged by illness, faced poverty, starvation and bitter temperatures, yet he never had a bad day in his life?

In part Zoosha's worldview is tempered by the fact that he has learned to accept that which he cannot change. Zoosha does not expect to be perfectly healthy, to live in wealth, to be well-fed, and to live forever. Instead, Zoosha's spiritual strength rests in his belief that each day of his life, no matter how difficult, is a blessing.

There is another story concerning Reb Zoosha that sheds light on the first.

Once a group of students asked him who his great heroes were--who they should emulate to achieve spiritual greatness. Zoosha replied, "When I go before the heavenly throne and the angels address me, I will not be asked, 'Why were you not like Abraham or like Isaac?'--I'll be asked,--'Why were you not like Zoosha?"

There are a number of interpretations of these two tales. One is that Reb Zoosha's spiritual approach is to live in the moment. In a Zen tale, a monk who is chased by a tiger to a ravine and holds on to a berry bush for his life remarks, "What beautiful berries!"--this is similar to Zoosha's ability to block out the poverty and decay around him and to live joyfully. One might claim that his life is spent denying power to the suffering around him. But others would remark that it is only Zoosha's ability to connect to a higher purpose that allows him to live to his fullest potential. Whatever your understanding of the Zoosha tales may be, the idea of finding some purpose in the journey with illness is clear.

The answer then to the "Why me?" question is another question: "What purpose will I find in this journey?"

Learning from suffering, though, seems like a position that no one in his or her right mind would choose to be in.

A frequent contributor to works on Jewish healing, Dr. Vanessa Ochs once offered these words:

My story is mine alone. It does not help when someone tells me I will learn from illness, that one day I shall be grateful.I know, too, that if I cannot make my experience meaningful in some fashion, it is really too trying to go on.