The official answer: One. Just one. I’ll explain. (If you’re wondering what Hardcore Dharma is, check out my introductory post).

Last night we concluded our discussion of the Eightfold Path by talking about the third sub-division of the path: samadhi, or meditation. Ethan began with the question, “Aren’t we always meditating?” When the scoffing died down, we talked about how this works.

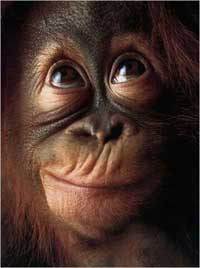

(Your mind is a room with a monkey. An evil, cute monkey.)

If we define meditation as the placing of the mind on an object, then in a sense we are always meditating. Our mind is constantly putting its attention on something. There are, however, more appropriate and less appropriate objects of meditation. Using Twitter as your object instead of, say, the breath or a chant probably won’t yield much in the way of spiritual satisfaction.

The frenetic, object-to-object nature of our minds has inspired many metaphors in the teachings. The mind is a wild horse. The mind is a wild boar. The mind is an energetic child. etc. Last night Ethan used one of my favorites (and one off his own creation?), the image of the monkey in the windowed room.

Imagine the mind is a room with six windows, one window for each of the senses (taste, touch, smell, hearing, sight) and one for thought, or thinking. In this room lives a monkey, a hyperactive, ill-disciplined monkey who is constantly jumping up and down, looking out one window, then another, and still another. He is receiving a near-continuous flow of information, but since he’s a short monkey and the windows are rather high, he’s only able to look out one window at a time.

Buddhist psychology posits that its impossible to look out two windows at once. In other words, we have the sensation of the simultaneity of perception, but its an illusion – the mind can only place its attention on one piece of sensory information at once. We might feel like multi-tasking is possible, but it’s not.

For example, I’m drinking tea in my favorite cafe (I have 3), taking a sip of hot liquid, listening to my friend vent about her boss and thinking about something to say that is both comforting and witty. And it feels like I can do it all at once.

In fact, I can’t. Or rather, I’m not. My monkey is simply jumping from window to window (tea to friend to inner dialogue) really fast. My mind does the work of making it seem continuous. Ethan suggested that this insight is backed up by findings in neuroscience: We receive sensory information out of order and our mind reshuffles it to create the illusion of narrative and cohesion. I think I’m listening to my friend with all my attention, but my attention is attached to the monkey, and he’s going nuts (as usual).

My reaction in class was, I’m not sure I agree. As I write, I can feel the sensation of my fingers tapping the keys at the same time as I compose the next words in my head. Is it simultaneous? It’s hard to tell. If I focus exclusively on the physical sensation, I stop writing. WIth concentration, I can half-hold two objects in mind, but it’s difficult.

Try it. Try to do two things at once that require your full attention, like cutting vegetables rapidly with an exceptionally sharp knife while having sex. Like I said: difficult.

Another metaphor for this phenomenon is a hard-drive (at least, how I think a hard-drive works): If you’re editing a video or building a playlist, the data is spread out over the entire disc space and the laser is jumping from point to point, assembling all the disparate bytes to complete your process. It appears to be continuous, but that’s just because we don’t experience the world at the speed of a spinning hard-drive.

Looking at perception this way can feel counter-intuitive and kind of radical, but it has important implications. If you’re going to try and settle your monkey-mind down and train it to tell the difference between being present and being lost in thought, it helps to understand how it works. Even if that means accepting the possibility that how we perceive the world is something of an illusion.