In my last post, I began to examine A Christmas Carol to discover why Ebenezer Scrooge changed so dramatically. I showed that we see the tiniest hint of his transformation in his interaction with the ghost of Jacob Marley, whose graciousness to Scrooge elicited a morsel of gratitude from the old miser. Yet Marley’s impact would be most keenly felt, not in his visit, but in his sending three other spirits to “haunt” Scrooge.

The Impact of the Ghost of Christmas Past

The Ghost of Christmas Past is a strange apparition who explains the purpose of his visit as Scrooge’s “welfare,” or, indeed, his “reclamation.” This process begins with an easily overlooked but crucial interchange between Scrooge and the Spirit. When the Spirit clasps Scrooge’s arm and begins to lead him towards the window, Scrooge resists, saying, “I am a mortal, and liable to fall.” Notice carefully the spirit’s response: “‘Bear but a touch of my hand there,’ said the Spirit, laying it upon his heart, ‘and you shall be upheld in more than this!'” The Spirit touches, not just Scrooge’s arm, but also his heart. And Scrooge would be upheld, not only in his supernatural travels, but also in the opening of his tightly-shut heart.

Then the Spirit magically transports Scrooge to the place where he spent his boyhood. The sights and sounds of his youth begin to soften Scrooge’s heart. Yet the Spirit has only started his transforming effort. Next Scrooge sees his fellow students merrily on their way to celebrate Christmas. The school is deserted, all except for one boy, “a solitary child, neglected by his friends.” It is Scrooge, of course, left alone with nothing to cheer him but the characters from his beloved books. The old man weeps bitter tears for the child he once was. For the first time in a long time he feels compassion for someone else, even if that “someone else” is really just an earlier version of himself. Yet, as he feels for himself as a boy, Scrooge also shows the first glimmer of care for another human being as well: “There was a boy singing a Christmas Carol at my door last night,” he explains to the ghost. “I should like to have given him something.” Ironically, Scrooge had almost given that boy something – a rap with his ruler!

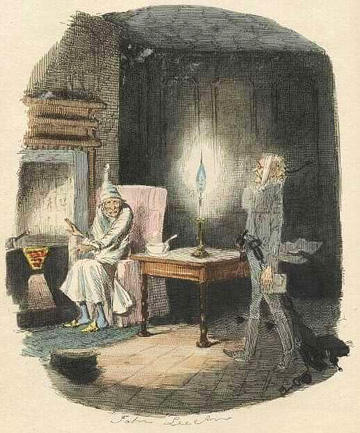

On some Christmas Eve following the time of his isolation in the school, the young Scrooge receives a visit from Fan, his beloved sister. (Dickens himself had a sister named Fanny.) Fan informs Ebenezer that he can come home for Christmas. (Years later Fan dies, leaving behind a child-the nephew Fred whom Scrooge had so badly mistreated only hours before.) (Photo: “Mr. Fezziwig’s Ball” by John Leech, from the first edition of A Christmas Carol.)

After this tender family scene, the Ghost of Christmas Past takes Scrooge to the warehouse of Old Fezziwig, to whom Scrooge had once been apprenticed. The mere sight of his generous old master brings joy to Scrooge’s heart. Then, as he witnesses a grand Christmas party, “Scrooge had acted like a man out of his wits. His heart and soul were in the scene. . . .” When the Ghost challenges Fezziwig’s actions, Scrooge defends his generosity. And, once again, this begins to be translated into a desire to be generous in his own life: “I should like to be able to say a word or two to my clerk just now,” Scrooge says.

The next scene is not a happy one for Scrooge. He watches as his fiancée, Belle, breaks their engagement, recognizing that Ebenezer loves money far more than he loves her. Then the Ghost shows Scrooge one more scene, in which a Belle is much older, with a husband and daughter. Their family love stands in stark contrast to Scrooge’s own miserly loneliness. At this, Scrooge begs to be removed. “I cannot bear it!” he exclaims.

How Do the Events of Stave II Transform Scrooge?

How does all of this help to transform the heart of Ebenezer Scrooge? His journey starts at a most curious place, with Scrooge looking upon himself as a lonely child. It’s as if Dickens realizes that even hard-hearted people might have the tiniest soft spot for themselves and their own suffering. One might almost be tempted to say that Scrooge is acting out a sort of psychological Golden Rule, loving himself so that he might love others as well. From a psychotherapeutic angle, Scrooge is getting in touch with his inner child.

The vision of the Fezziwigs’ party not only lures Scrooge into a bit of vicarious celebration, but also it forces him to reexamine his own values. Mr. Fezziwig, whom the old Scrooge continues to hold in high regard, saw fit to spend a bit of money for the sake of others. “The happiness he gives,” Scrooge insists, “is quite as great as if it cost a fortune.” There’s more to life than money, the old miser begins to realize for the first time in a long time.

The Ghost of Christmas past, beyond conjuring up within Scrooge feelings of nostalgia and celebration, helps him see-and feel-the harsh contrast between love and loneliness. Love figures prominently in his boyhood encounter with his sister Fan. Remembering her love for him-and his for her-makes Scrooge’s grouchy rejection of Fan’s son Fred all the more grievous. Moreover, the scenes featuring Belle press into Scrooge’s heart the lack of love in his own life. Where Scrooge had once felt genuine love (from and for Fan, from and for Belle), he had chosen to cut himself off from this love, whether with his former fiancée, or with Fred. He realizes he has made poor choices for his life, and he starts to wish for something better.

It’s interesting to me that Scrooge doesn’t reject all of this as a bunch of maudlin nonsense. What, I wonder, gives him the ability to see, really to see, his life as it truly was? And what gives him the ability to feel emotions that had for so long been absent from his heart? Yes, seeing himself as a hurting young boy might very well have opened Scrooge’s heart a bit. But this might not have happened were in not for the earlier intervention of the Spirit, when he touched Scrooge’s heart and promised that he would be “upheld” in more than just their other-worldly travel.

Theological Reflections

What can transform a stony heart? For Charles Dickens, the answer has several layers. Nostalgia for the past seems to help. Looking afresh at one’s life makes a difference. Supernatural assistance contributes. But, at the core, love changes people. Love, not of the romantic sort, but of the compassionate, self-giving variety, transforms hearts. When Scrooge witnesses the love of his sister Fan and his master Fezziwig, something happens inside of him. And when he sees how he spurned the love of his former fiancée and how happy she is with a loving husband and daughter, Scrooge realizes how much he has lost be shutting his heart to love.

Here, once again, Dickens’s anthropology is virtually Christian. Christians believe that ultimate transformation in life comes as we experience God’s love for us given through Jesus Christ. Over a century before Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol, another Englishman had something to say about the power of love to transform one’s life. Consider how these words of hymn writer Isaac Watts express something like what happened to Ebenezer Scrooge:

When I survey the wondrous cross

On which the Prince of glory died,

My richest gain I count but loss,

And pour contempt on all my pride. . . .Were the whole realm of nature mine,

That were a present far too small;

Love so amazing, so divine,

Demands my soul, my life, my all.

For the Christian, the deepest and most transforming kind of love is celebrated, not at Christmas, but on Good Friday. Christmas is what makes Good Friday possible, as the Son of God chooses to love by enduring the cross.