In my last post I introduced Matthew 18:15-17, a passage in which Jesus talks about what to do if someone sins against you, and made some preliminary remarks. Today I start examining the text itself. The whole passage reads:

“If another member of the church sins against you, go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone. If the member listens to you, you have regained that one. But if you are not listened to, take one or two others along with you, so that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. If the member refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if the offender refuses to listen even to the church, let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.” (Matthew 18:15-17, NRSV)

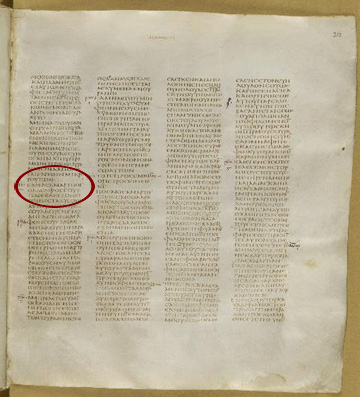

“If another member of the church”

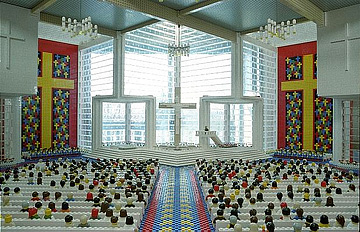

As I explained in my last post, the Greek underneath this English phrase reads simply, “if your brother” (ean . . . ho adelphos sou). Since it’s clear that Jesus includes both males and females within the scope of his instruction, the NRSV translators use “another member of the church” in place of the literal “brother.” Notice that Jesus is not talking in this passage about every possible relationship, but only the relationships between people within his family, which is to say, between Christians. This text simply doesn’t speak to the question of how you might deal with a non-Christian who mistreats you. (Of course the principles of this passage may well guide us in our relationships with those who are not believers, even if this is not Jesus’ main point.)

Although the NRSV guards the potential misunderstanding of “brother” as “male Christian,” it misses the family nuance, as does the NLT’s “another believer.” The TNIV maintains the more intimate sense by using “brother or sister.” This matters because Jesus is assuming that the person who wrongs you isn’t just a fellow church member or believer, but a sibling. If you think about the one who wrongs you as a member of your family, then your response to that person may very differ from what you’d do with someone outside of your family.

I think, for example, of a time a few years ago when I said something mean to one of my sisters (a literal sister). Now if I’d been just anybody, she might have decided that it wasn’t worth the hassle of confrontation. But because I was her brother and part of her family whether she liked it or not at that moment, she risked telling me what I had said and how it hurt her feelings. Our family relationship called forth honesty and mutual commitment. “So it is within my family,” Jesus is saying. Since the one who has sinned against you is your brother or sister, it’s really not an option for you to write that person off.

“Sins against you”

In my last post discussed the possibility that “against you” didn’t appear in the original text of Matthew. I explained why this option doesn’t matter all that much to our current investigation. But what about the verb “to sin”? How should we understand this verb? How can I know if someone has sinned against me? Isn’t sin always against God?

Simply put, the verb “to sin” means to do something contrary to God’s will. All sin, therefore, is, first and foremost, sin against God. But many kinds of sin also impact other people. Consider the Ten Commandments. If I don’t honor my mother and father, I am sinning against the Lord and against them. If I murder someone, I’m committing wrong against God and my victim. And so forth and so on. Therefore, someone has sinned against you when that person has done a wrong deed that has negatively impacted you.

In certain cases it’s pretty easy to determine if someone has sinned against you. Murder, adultery, stealing – it will be clear if you’re a victim of such things. But in other cases it’s much harder to know if somebody has sinned against you or not. You may not know if someone has lied about you unless you hear of it. And you may be unaware that somebody is coveting your stuff. Nevertheless, if it can be determined that lying or coveting have happened, then you’re clearly in the “sins against you” category of behavior, and Jesus advice speaks directly to your situation. (Photo: My son and I enjoying our new bikes. Unfortunately, we took these bikes with us on a vacation to San Francisco. Though they were locked up, thieves managed to cut the locks and steal our bikes. Needless to say, we weren’t able to go the thieves and confront them.)

But what about cases that aren’t even this clear? What about when you feel offended by what someone has said, even if this person never intended to create offense? What if you hear through the grapevine that someone has been gossiping about you, but you’re not sure the gossip you’ve heard can be trusted? There aren’t easy answers to these questions. On the one hand, I don’t think Jesus envisioned a community of disciples in which every little peccadillo deserved a full frontal confrontation. On the other hand, I know that we sometimes avoid the directness of Matthew 18:15-17 by rationalizing, “Oh, what that person did really wasn’t a sin, so I don’t need to talk to him about it.” Yet we end up harboring resentment in our heart for that person, weakening both our relationship with him and the church in general.

When a fellow Christian’s behavior is clearly sinful, at least insofar as you can tell, and you are in some measure a victim of that behavior, then you are obligated by Jesus to act upon his advice. When you’ve been hurt by someone’s behavior even when it may or may not have been sinful, the obligation isn’t quite as definite. But I think the underlying principle of Jesus points to the need for a direct, face-to-face conversation, even if it takes on a different tone than Matthew 18:15-17.

I cannot tell you how many times I’ve seen a Christian sister hurt another sister inadvertently. The victim, though truly hurt, doesn’t want to engage in awkward and risky confrontation, so she chooses instead to try to ignore the offense. But the hurt in her heart is real. So she ends up building a wall of resentment and protection between herself and the one who hurt her. In many cases, I’ve intervened and encouraged the victim to talk with the perpetrator. Yet I often hear an excuse like, “But what she did really wasn’t a sin, so I don’t have to confront her.” That sounds easy enough, except the broken relationship between the sisters is causing damage, not only to them and their mutual friends, but also to the whole church.

If you’re a person who tends to overreact and accuse others of wrongdoing, you may want to be sure you’re not misusing Matthew 18 by confronting those who haven’t done anything wrong to you. On the contrary, if you’re someone who tends to avoid conflict at all costs – someone like, me, for instance – watch out for your own denial and rationalization. The health of the church, not to mention your own ultimate well being, may very well require that you do the risky thing and talk directly to the one who has hurt you.