My father-in-law turned six on the morning that the Japanese Air Force destroyed the US Naval base at Pearl Harbor. As a child, it was a day of expectation. For the rest of his life it has been a bitter-sweet day, as he has both celebrated his years and recalled the death of so many young Americans. My parents were sitting in a high school classroom on a November afternoon in 1963, when the principal broke in over the public address system to announce the news that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas, Texas. These teenagers, so far removed from the world stage and politics, wept and cried. The entire nation did.

My father-in-law turned six on the morning that the Japanese Air Force destroyed the US Naval base at Pearl Harbor. As a child, it was a day of expectation. For the rest of his life it has been a bitter-sweet day, as he has both celebrated his years and recalled the death of so many young Americans. My parents were sitting in a high school classroom on a November afternoon in 1963, when the principal broke in over the public address system to announce the news that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas, Texas. These teenagers, so far removed from the world stage and politics, wept and cried. The entire nation did.

In January 1986, I was a high school student spending the day at my grandmother’s house. It was a rare snow day in Georgia. There were probably three flakes on the ground, but that was enough to paralyze half the state. I was watching television on her old, cabinet set. I had already been outside in the cold once to manually turn the antenna pole toward Atlanta. Ice prevented the automated dial from working (some younger readers have no idea what I am talking about here). I had just settled down to watch the Space Shuttle Challenger lift off with Christa McAuliffe, a social studies teacher, on board. In her second minute of flight, the Challenger exploded over the Atlantic Ocean.

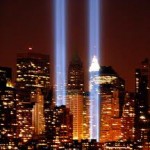

Of course, who of us can remove from our minds the images of burning towers, or of the concrete dust and ash falling overManhattan? Only the youngest among us have no memory of that catastrophe. Where were you when you first heard the news? What did you feel? How long did it take to get your mind around what was happening on an otherwise beautiful Tuesday morning?

When tragedies like these take place, I find myself asking those questions most of us ask: Why? Why here? Why now? Why them? Why do things have to be this way? Sure, we can talk about faulty O-rings, imperialism, assassination conspiracies, even the religio-social dynamics that breed terrorism, but these do not explain so much of the unfair heartache and injustice in our world. Often, more times than not, there is no answer to these questions. Jesus once spoke of a falling tower whose collapse killed a number of unsuspecting victims. There were those who felt this must have been a divine retribution for some terrible sin. The prevailing conclusion of Jesus’ day was those who suffer do so because they have God aligned against them. This was the only explanation behind otherwise inexplicable tragedy.

This way of thinking is known as lex talionis: The “law of the talon,” the law of retribution. One’s suffering in this life was indicative of how sinful they were. Thus, those who prosper are righteous and those who suffer are evil. Following this line of thought, many of Jesus’ listeners would conclude that the astronauts on the Space Shuttle were terrible sinners, and that is why they perished. Those who did not escape the burning towers on September 11th were destined for destruction because they were evil. Those young sailors who were shot to pieces or drowned on that Sunday morning in 1941 got what they deserved. It is a shocking, calloused way of thinking.

Jesus rejected any easy-answer conclusion that tragedy is always the result of overt sin on the part of those who suffer. Granted, Jesus did not tell us why towers fall on the innocent. He did not tell us why unsuspecting astronauts meet a fiery crash, or why some escape the destruction of terrorists’ attacks and others do not, or why tornados hop and skip over one home only to land in full force on another. He did not go there at all, like some flaming television evangelist boldly explaining famine, earthquake, or tsunami as divine judgment. Instead, Jesus revealed with his life and words a God who did not arbitrarily smite the powerless, but he joined them in their suffering.