In previous articles, I described the experience in the temples of dream healing of the ancient Mediterranean. After an encounter with the sacred healer – who might appear as a figure of living gold, or a dog or a snake, or a beautiful woman, or a radiant boy – it was customary for those who had been privileged to live this experience to offer votive objects and testimonials. At some sites, the beneficiaries were seated on a “throne of memory” to recount the events of the sacred night.

The most loquacious of those who spoke of such things was Aelius Aristides, renowned as an orator in an age when a popular speech-maker had something of the glamor of a movie star.

In one of his most powerful dream visions, the orator saw the god of healing as a living statue with three heads: “The cult statue appeared to have three heads and to shine about with fire, except for the heads.” The worshippers stood before it, ready to sing the paean, the hymn of praise for the divine healer. The god gestured for them to leave, then signaled with his hand for Aristides to stay. Thrilled at this honor, Aristides called out his praise.

“I shouted out, ‘The One’, meaning the god. But he said, ‘It is you.’”

The orator wrote of this experience: “This was greater than life itself, and every disease was less than this, every grace was less than this. This made me able and willing to live.”

Written in a lucid, simple Greek that was taken for a model of composition, Aelius Aristides’ Sacred Tales [Hieroi logoi] are a travelogue through the landscapes of illness and healing. They are a literal travelogue; we follow him through night journeys by carriage, and naps in his dusty traveling clothes in a folding chair in front of darkened hostelries, and temple visits and attempted cures. They are also a narrative of travel in an alternate reality, opened by dreams and visions.

Always, he is walking with, or seeking, the god he can talk to. In his early life, the name of that god was Serapis, whose cult I describe in my Secret History of Dreaming (and who may be the original “angel that troubles the waters” at the pool of Bethesda); later, the god was Asklepios. One of the gifts of the divine healer and his prescriptions, as reported by Aelius Aristides, was raw energy. After the god directed him to bathe in a river in midwinter, he felt “an unspeakable sense of well-being, which made everything fade in the face of the present, so entirely was I with the god.”

Many of his big experiences came in “an intermediate state between sleep and waking” with “the hair on end and tears of joy and an inward swelling of delight. Those who are of the initiated will understand and recognize it.”

In his Orations, Aelius Aristides gave this memorable account of what it was like to come face to face with the god of dream healing: “I seemed almost to touch him. Halfway between sleep and waking, I perceived that he was there in person; one was between sleep and waking. I wanted to open one’s eyes but I was anxious that he might leave. I listened and heard things, sometimes as in a dream, sometimes as in waking vision. My hair stood on end, and I wept tears of joy, and the weight of knowledge was no burden.” In his awe, the wordsmith asks, “Who can put this experience into words? Only if you have been through it can you know and understand.”

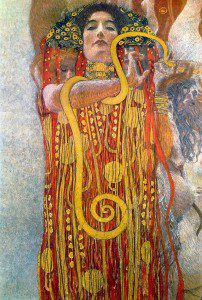

The names of the daughters of Asklepios, Hygeia and Panacea, survive in our common language, though Hygeia becomes “hygiene”. However, the name of Asklepios, in the Greek or the Roman version (Aesculapius) is largely forgotten in our modern Western culture.,

Early Christians, however, were very familiar with Asklepios. He was major competition. According to Morton Smith, author of Jesus the Magician, some of the earliest known images of Christ were statues of Asklepios that had been renamed. In preaching among gentiles, early Christians appealed to the resemblance between Christ and Asklepios as divine healers. Justinus noted that when the gentiles were told that Jesus performed healings and raised the dead, “they brought forward Asklepios.” He recommended that Christians should give the following response: “We propose nothing new and different from what you believe about those you esteem sons of Jupiter. Asklepios was a great healer. Struck by a thunderbolt, he ascended to heaven.”

In Dreaming in Late Antiquity, Patricia Cox Miller observed that Asklepios “lived on in the cult of the saints.” There was a spectacular case of appropriation in cult of St Thecla in Seleucia, on the Mediterranean coast of what is now Turkey. In early Christian legend, she was converted by Paul, a strong opponent of the great healing temples of that coast. Ironically, Thecla became the patron saint of a dream incubation center, healing by appearing in dreams to the sick who slept in her church, and working miracles.

The name of Asklepios may no longer be a household word, but when physicians take the Hippocratic oath they are repeating words originally addressed to Asklepios and his father Apollo, as Paian or All-Healer. And the symbol of Asklepios is everywhere in our modern world, on the side of EMS trucks, on the doors of hospitals, on the letterhead of clinics and insurance companies. It is a single serpent wrapped around a staff, not to be confused with the double serpent of the caduceus, the emblem of Hermes or Mercury. The rod of Asklepios speaks of our need to harness and raise the serpent energy, to borrow the snake’s ability to shed the skin of the old life, and to discern when poison is medicine, and when medicine is poison.

We will open the Temple of Dream Healing at a lovely private retreat center near Seattle from July 16-20. Then we will join in even deeper experiences of Asklepian healing at a beautiful site on the Aegean coast of Turkey from September 28-October 2.