Seeing the reference to Van Gogh sunflowers in my poem “A Way of Creating” – which was inspired by a dream encounter with Van Gogh reported by an artist in one of my workshops – a friend reminds me that we now have a marvelous online source on the wellsprings of Van Gogh’s creative process. This is the beautifully edited and translated collection of his letters first made available in 2009 by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Seeing the reference to Van Gogh sunflowers in my poem “A Way of Creating” – which was inspired by a dream encounter with Van Gogh reported by an artist in one of my workshops – a friend reminds me that we now have a marvelous online source on the wellsprings of Van Gogh’s creative process. This is the beautifully edited and translated collection of his letters first made available in 2009 by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

In his letters, Van Gogh speaks of dreams, in his own life and in the lives of other artists. Writing to his brother, he recalls how Corot explained that he colored skies entirely pink because he dreamed them that way:

When good père Corot said a few days before he died: last night I saw in my dreams landscapes with entirely pink skies, well, didn’t they come, those pink skies, and yellow and green into the bargain, in Impressionist landscapes? All this is to say there are things one senses in the future and that really come about. [Letter 611 to Theo Van Gogh, May 20, 1888]

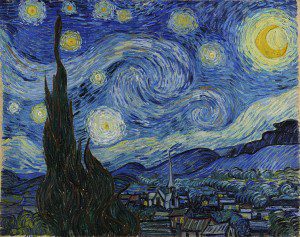

The sight of the stars always makes me dream in as simple a way as the black spots on the map, representing towns and villages, make me dream. Why, I say to myself, should the spots of light in the firmament be less accessible to us than the black spots on the map of France.

Just as we take the train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star. What’s certainly true in this argument is that while alive, we cannot go to a star, any more than once dead we’d be able to take the train. So it seems to me not impossible that cholera, the stone, consumption, cancer are celestial means of locomotion, just as steamboats, omnibuses and the railway are terrestrial ones.

To die peacefully of old age would be to go there on foot. [Letter 638 To Theo, July 9/10, 1888]

“We take death to go to a star.” That phrase will be with me now, whenever I look at Van Gogh’s starry skies.