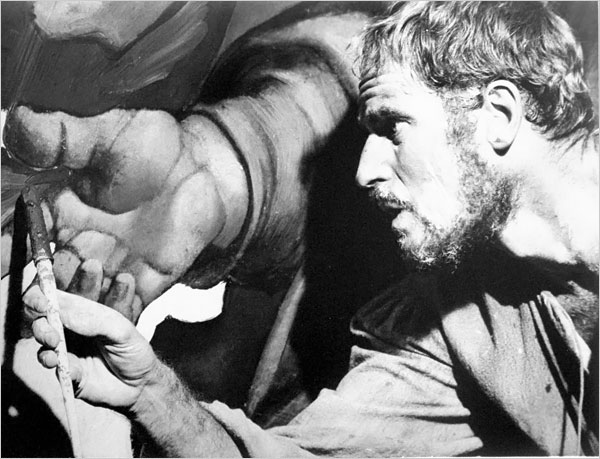

The obituaries for Charlton Heston tend to play up his larger-than-life roles, such as the fearsome, bearded Moses or the powerful, bare-chested Ben-Hur, or the noble, doomed El Cid. I always think of him as the passionate, difficult genius Michelangelo, playing opposite Rex Harrison as Pope Julius II (now there’s a pope) in “The Agony and the Ecstasy” of 1965. Apart from my love of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the creation o which is the focus of the film, my connection of Heston with that movie is surely because the closest I ever came to the actor was while I was working at Vatican Radio in the late 1980s, the same time the Vatican was having the Sistine Chapel restored (or cleaned, or damaged, depending on how you view it). (AP photo via NYTimes)

The obituaries for Charlton Heston tend to play up his larger-than-life roles, such as the fearsome, bearded Moses or the powerful, bare-chested Ben-Hur, or the noble, doomed El Cid. I always think of him as the passionate, difficult genius Michelangelo, playing opposite Rex Harrison as Pope Julius II (now there’s a pope) in “The Agony and the Ecstasy” of 1965. Apart from my love of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the creation o which is the focus of the film, my connection of Heston with that movie is surely because the closest I ever came to the actor was while I was working at Vatican Radio in the late 1980s, the same time the Vatican was having the Sistine Chapel restored (or cleaned, or damaged, depending on how you view it). (AP photo via NYTimes)

Any story about the chapel was a great one to report, natch, and when we heard that Charlton Heston was in town, the stars–so to speak–had aligned…

Yet somehow my colleague, Lana, an L.A. native with ties to the entertainment biz (she was named after Lana Turner), always managed to score the celeb assignments. And so it was with Heston. We worker bees set about putting out a news broadcast, while Lana disappeared up in the Vatican somewhere to meet “Chuck.” And sure enough, she came back glowing a few hours later (we were sweating; live broadcasts do that to you). Not only had she convinced Heston to give her an interview, but she managed to have the Sistine Chapel opened after closing time for a private tour. It wasn’t that hard, really. Vatican officials get as star-struck as anyone, and a mention of Heston’s name in a call to the archbishop in charge of the chapel set His Excellency atwitter and before they knew it, the doors of the chapel swung open, and Lana and Chuck (and the monsignor, presumably) even went up on the scaffolding for a close-up of the restoration process.

The interview was of course a keeper. But the best bit was when Heston explained that in order to create the illusion that he (as Michelangelo) was painting the ceiling lunette by lunette, they photographed the entire frescoed expanse and reproduced it on a sound stage ceiling. After each day’s shooting they would then plaster over a lunette, until the end of the film the entire ceiling was a “blank canvas” of white fresco. Then in the editing suite they cut the scenes in reverse order, so it appeared that Heston was painting a plain white ceiling bit by grueling bit, covering it in stunning images, rather than the reverse, as they filmed it. (I hope that makes sense.)

In any case, what was really fascinating is that until that interview, Heston had never seen (as none of us had) the ceiling as Michelangelo painted it, in all its brilliance. Indeed, the “glorious” ceiling that emerges (or submerges, as the case was) from the film version is actually the sooty, muted version we–and art scholars–grew up with.

So what did I report on that day instead of Charlton Heston’s return to la Sistina? Who knows? Who cares?